Revolution in the Cross’s Shadow: Solidarity as Performance

Prayer at August strikes, Gdańsk Shipyard, 1980. Photographer unknown / collection of the European Solidarity Centre.

The text is a fragment of a chapter from Marcin Kościelniak’s book Egoiści. Trzecia droga w kulturze polskiej lat 80 [Egoists. A Third Way in Polish Culture of the 1980s]. In the book, the author considers the first Solidarity movement in terms of its complex relationship with the Church and Catholicism, analysed at the level of signs and symbols it used, traditions it refered to, rhetoric it applied, as well as in the area of social practices and rituals it employed. Paying close attention to the extremely intense and almost universally accepted presence of the religious (and national-religious) discourse in Solidarity’s discourse, the author endeavours to problematize the widely accepted opinion of the first Solidarity as a universal, pluralistic, fully democratic movement. Viewing Solidarity as a cultural identity performance is at the same time an attempt at the genealogy of Polish modernity.

Is a different Republic possible?

In his book Liberalizm po komunizmie [Liberalism after Communism], Jerzy Szacki recalls a dispute between supporters of the ‘conviction of the socialist character of the Solidarity movement’ and the view that Solidarity stood against true socialism by displaying Christian and national slogans.1 At the same time, as referred to by Paweł Rojek in Semiotyka Solidarności [The Semiotics of Solidarity], the dispute takes place between supporters of the narrative of Solidarity as a pluralist and democratic movement and those who view the Solidarity movement as ‘illiberal and contrary to European values’.2 ‘Some statements pertaining to this movement are so divergent that it is hard to believe their authors speak about the same phenomenon’,3 writes Rojek.

The dispute has recently been resumed by Jan Sowa in his interesting book Inna Rzeczpospolita jest możliwa! [A Different Republic Is Possible!]. He writes of Solidarity as a socialist movement of a ‘syncretic nature.’4 ‘The world for which Solidarity fought at the beginning of the 1980s was not at all built on the principles of a religious state, and drew primarily from the idea of an autonomous labour movement’, whereas ‘militant nationalism and religious fundamentalism were relegated to the absolute margins’,5 writes Sowa. ‘Right are those who think that for several months between August 1980 and December 1981, Poland was the most democratic place in the world’,6 he claims, espousing the still popular and definitely dominant community-founding myth of Solidarity. Sowa makes his narrative a part of the political project of ‘a different Republic’, which is close to me in many ways and this precisely why I enter into polemics with it. I shall follow the lead of those voices that pointed out to a diametrically different character of Solidarity. ‘Within 500 days the analysed movement evolved towards the slogan […]: Under the sign of Solidarity, Poland is Poland and a Pole is a Pole’, Marcin Kula wrote in 1988, pointing out that ‘national content and slogans have been present in this movement from the very beginning. They were present in the fundamental bywords of August [1980], such as dignity, freedom, truth, human rights, subjectivity, justice, common sense and, last but not least, solidarity’.7 ‘Revolution in the cross’s shadow’, ‘a moral crusade’, ‘a great national church gathering’, a movement born ‘kneeling with rosary in hand’8 – these are the directions I will follow.

The links between Solidarity and the Catholic Church were obviously not formalized – not in the sense that the representative of the Mazovia Regional Solidarity leadership had in mind in 1980 when he asserted that ‘the Episcopate does not strive to create Christian trade unions’. Although, he added, ‘it would be relatively easy to do so’. After all, he pointed out, there is ‘a danger, and there are facts testifying to how real it is, that the regeneration of the union movement would then be limited to certain symbols (“Christian” in name, portraits of the pope, etc.)’.9 This is precisely the dimension in Solidarity discourse that interests me. I am also interested in the immanent and intense presence of religious symbols and the church in the Solidarity movement, as well as the practice of continuous reference – institutionalised and spontaneous – to Christian-national values […]. My intention is not a panoramic or conclusive approach, but rather to indicate several places in which the merging of political and religious discourse is revealed as key for understanding Solidarity’s identity. At the same time, by narrowing the perspective in this way, I want to move beyond thinking in binary terms. The point is not whether Solidarity was totalitarian or democratic, national-democratic or liberal. The point is to show that widely accepted limitations were written into Solidarity’s ideology and its practice of pluralism – making it, one might say, a limited pluralism – and to show that even today’s thesis about Solidarity’s pluralism is often formulated at the level of a symbolic universe whose invisible limits determine the existence of a common ground for each individuality. My aim is to attempt to indicate these limits.

The limits of debate

‘Where else but in communist Poland would a strike be launched with Holy Mass and lines from Byron’,10 wrote Timothy Garton Ash, recalling that after the mass celebrated by Father Jankowski on 17 August [1980], a cross was erected in front of the shipyard gate, decorated with the image of the Virgin Mary and a sheet of paper with an excerpt from [Byron’s] The Giaour translated by the Polish Romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz. From among many extant images and reports from the strike that might be recalled here, I will quote a large excerpt from Kto tu wpuścił dziennikarzy [Who Let the Press in Here] that includes journalists’ reports written on the spot:

W[ojciech]. Giełżyński: The role of the church in the strike was evident right from the moment you entered through the shipyard gate, decorated with portraits of the pope and images of the Virgin Mary, dressed with flowers. […] A cross hung on the wall behind the presidium. In a word, religious accents were visible at every step. Masses took place every day in the morning and in the afternoon. The priests came from a nearby parish.

A[ndrzej]. Zajączkowski: Confessions made a particularly shocking impression. A car would simply pull up with a sign saying Pastoral help – priests would come out of it, sit on small folding chairs and hear confessions.

P[iotr]. Halbersztat: I have a picture in which one of the shipyard workers literally cuddles up to the confessor’s shoulder. There is no confessional, and the confession – after all, an intimate matter – takes place amongst the crowd and in front of its eyes.

Giełżyński: They confessed, they gave communion, and in the moments of greatest tension – even performed the last anointing.

Z[bigniew]. Trybek: The masses were amazing. The greatest impression was made when they were all kneeling as they sang ‘Rota’[‘The Oath’] and ‘Boże coś Polskę’ [‘God Save Poland’]. When you looked at the workers, how they cried singing ‘God Save Poland’, it really tugged at your heartstrings.

Giełżyński: There was one mass when the priest was chanting the confession of faith, and at the same time the speaker through which messages were broadcast was switched on. It looked more or less like this: ‘I believe in God, the Almighty Father’… ‘Ostrów Wielkopolski is with us’, ‘Creator of Heaven and Earth…’, ‘We have placed 80,315 Polish złotys in your account…’ […]. It was affecting.

N[ina]. Rasz: The prayer of the crowd. It has always been a moving experience for me. Young girls from the pastoral ministry would say a litany and the crowd would repeat it.

Zajączkowski: Every day something along the lines of a political rosary took place. Without the presence of priests, the workers gathered and recited a litany to Virgin Mary in some current intention. [...] A prayer for the homeland was always said as well. This Christian atmosphere persisted throughout the strike.

J[anina]. Słuszniak: How to understand this explosion of religious sentiment, this virtually religious demonstration? All historical events require a framework, a ceremony. And suddenly it turned out that the moral protest of the society does not find any official form that would not have been discredited. Only the church turned out to be an institution that did not betray the national interest.11

Decorated gate at August strikes, Gdańsk Shipyard, 1980. Photographer unknown / collection of the European Solidarity Centre.

The symbolic closure to the shipyard performance was the fact that the August accords were signed by Lech Wałęsa (wearing a rosary around his neck) with a soon-to-be famous pen bearing Polish national colours and an image of Pope John Paul II. ‘The Gdańsk strike became [...] an extension of this holiday, which began in the days of the papal pilgrimage: the atmosphere was the same, as were the ritual and the signs’,12 writes Andrzej Kijowski in an essay from 1982.

‘This nation that wants to stand on its own feet can also fall on its knees’, as France catholique, Ecclesia commented at the time on role of the church and religious symbols in the strike.13 The calendar of 500 days of the Solidarity carnival is filled to the brim with official meetings of union delegates with church hierarchs: Primate Stefan Wyszyński, Primate Józef Glemp, John Paul II, the bishops. The rite of Catholic mass became an inseparable element of both union and national anniversaries and ceremonies: remembrance of the December 1970 victims in Gdańsk,14 Gdynia and Szczecin, unveiling the monument to 1956 [protest] events in Poznań, the registration of Rural Solidarity, celebrations of the anniversary of the 31 August accords, the anniversary of the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, annual national commemorations on 11 November, as well as 1 May and 3 May.15

Regional trade-union bulletins as well as the Pismo Okólne [Circular Diary] of the Polish Episcopate report almost every week of the ‘carnival’ period some ecclesiastical celebration connected to Solidarity: masses to the intentions of Solidarity ordered by trade unionists, masses celebrated in workplaces, acts of devotion to Our Lady of Częstochowa16, consecration of portraits of St. Barbara in Silesian mines, consecration of crosses, banners and Solidarity offices in various places in Poland. The banner of the Inter-trade Strike Committee, consecrated by Archbishop Franciszek Macharski during the unveiling of the Monument to the Fallen Shipyard Workers in Gdańsk, represented a typical combination for many regional banners and is symbolic of Solidarity itself: ‘on one side, an image of Our Lady of Częstochowa against a white-blue background, on the other, the Polish national eagle against a white-and-red background’.17

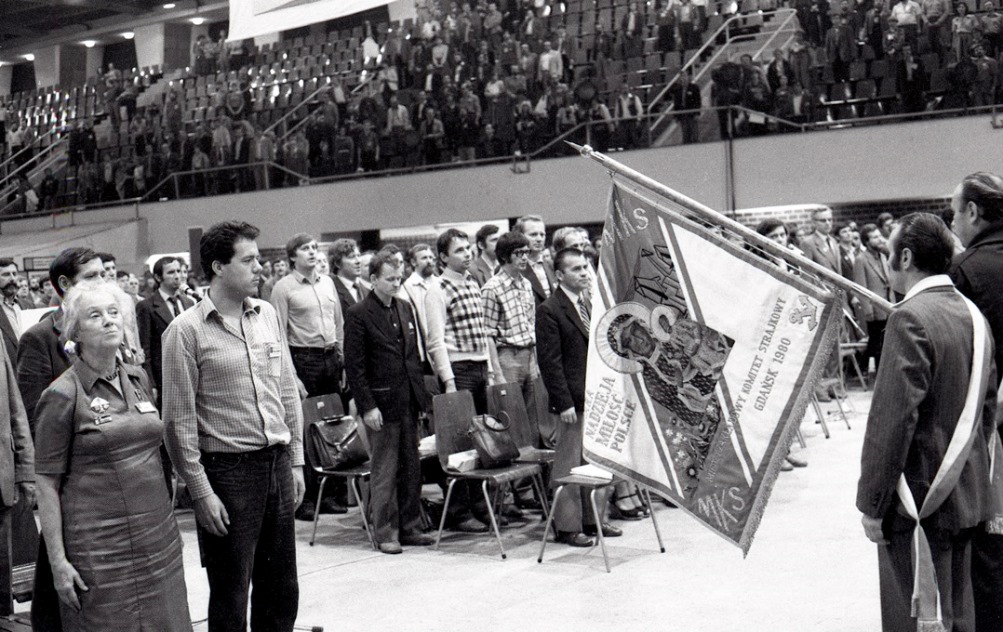

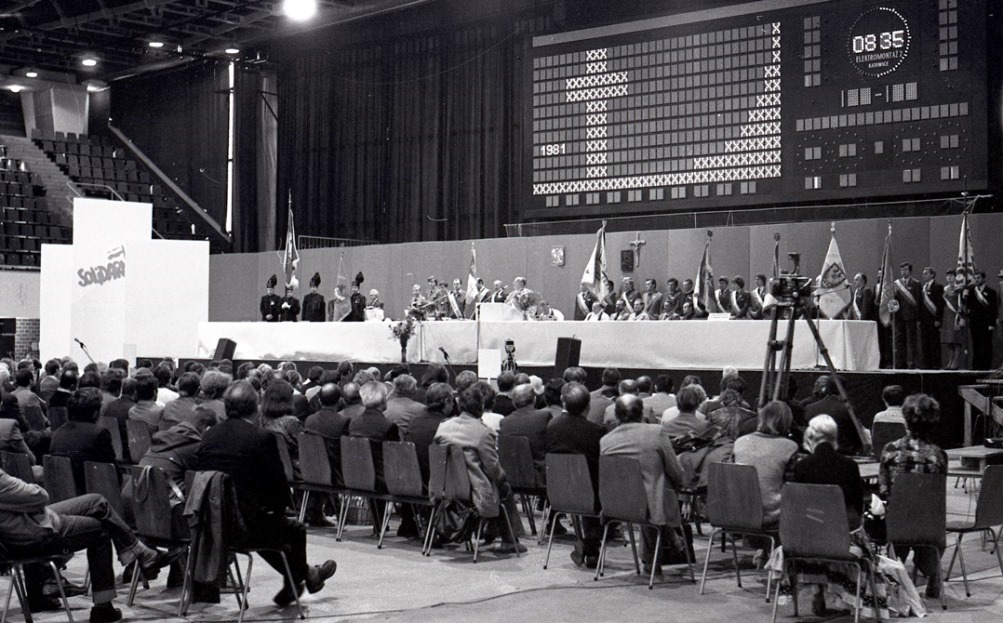

First National Congress of Solidarity, September-October 1981. Photo: Giedymin Jabłoński / collection of the European Solidarity Centre.

First National Congress of Solidarity, September-October 1981. Photo: Giedymin Jabłoński / collection of the European Solidarity Centre.

It is hard to deny the religious face of Solidarity18 – it is therefore essential to understand it. ‘[The r]eligious face of the Tri-City strike must have been visible to every observer. It actually took place in the cross’s shadow’, wrote the editors of the national-independence magazine Bratniak in 1980, stating with satisfaction: ‘Once again it was confirmed that the Polish nation is a Catholic nation and such is the very nature of its working class’.19 The ‘left’ wing argued that the Polish Church was not a spokesperson for Catholicism as a set of national values, but rather of Christianity as a set of universal values which do not clash with the pluralistic face of the union. ‘The cross cannot become a symbol of difference’ but of ‘reconciliation’, stated an article printed in 1981 by the Solidarity Press Agency bulletin, in which the author was assuring that ‘people thinking differently than Christians’ can remain ‘Marxists, communists and atheists’, because the cross ‘encompasses everyone’.20 These statements mark the limits of debate on the presence of the church and of religious discourse in Solidarity. These limits are seen most clearly when quoting the leftist Workers Vanguard: ‘only a blind man could fail to see the gross influence of the Catholic Church and also pro-Western sentiments among the striking workers’, states the magazine in its first account of 1980 events in Poland, then continues to decree: ‘If the settlement strengthens the working-class organisationally, it also strengthens the forces of reaction. Poland stands today on a razor’s edge’.21 As shall be indicated further on, any similar voice in Poland, if another was ever uttered, did so only with a series of reservations and justifications, on the principle of an exception confirming the rule. Of course, this does not apply to the Communist press – which is an important context, but certainly not enough to understand the nature of the Polish democratic agora at the time.

The limits of syncretism

Speaking on 11 December 1981 at the Congress of Polish Culture22 about the ‘surprising update’ of Romantic-era culture traits in August and post-August culture, the Polish professor of literary history Maria Janion pointed to its religious wing. Noting the remarkable ‘major spiritual focus, even taking the form of religious exaltation’ among the strikers, as well as ‘the working-class community in the grips of a religious and patriotic rapture’, Janion juxtaposed it with the ‘stereotype’ testifying to the fact that ‘religion belongs organically to the apparatus of the ideological oppression of the masses’.23 ‘Communists, socialists or Christian Democrats in Italy, or even France, cannot get their heads around the fact that workers pray while they strike. They listen to the Holy Mass, beat their breasts, strengthen themselves with the Body of Christ? But these are irreconcilable things! – It turns out that they are in fact compatible’,24 stated Primate Stefan Wyszyński at the end of 1980.

Jan Sowa, like many other researchers, writes about the syncretism of Solidarity. Sowa also puts forward a thesis on its socialist origin, which he proves mainly on the basis of the program resolution of the First National Congress of Delegates of the Solidarity Independent Self-governing Labour Union25 from 7 October 1981, including the document ‘Self-governing Republic’. I do not argue with this thesis – postulates of the union’s social origins were a part of Solidarity discourse (the banner hung above the Lenin Shipyard gate, ‘Workers of the factories, unite!’, was not necessarily ironic, as claimed by the creators of the permanent exhibition of the European Solidarity Centre in Gdańsk), while democratic demands constituted its core. I merely want to point out that in the very first point of its program (‘Who are we and where are we going’), along with declarations that ‘the “Solidarity” Independent Self-governing Labour Union unites many social movements and connects people with different worldviews, different political and religious beliefs, regardless of nationality’, the following note appears:

Solidarity, by defining its aspirations, draws from the values of Christian ethics, from our national tradition, as well as the working-class and democratic tradition of the world of labour. John Paul II’s new encyclical about human work constitutes a fresh impetus for us. Solidarity as a mass organisation of working people is also a movement of moral revival of the nation.26

We find similar logic in, for example, the ‘Program Declaration on National Culture’ from October 7, where the proclamation of neutrality as a safeguard for tolerance is accompanied by another argument:

Bearing in mind that we have been introduced to our wider motherland – Europe – by Christianity, and that Christianity has determined to a large extent the shape and content of Polish national culture, and that in its most tragic moments the nation could find support in the Catholic Church, that our ethics is first and foremost determined by Christianity, and finally that Catholicism is the living faith of the majority of Poles – we believe that in the process of national education it is necessary to honour and properly acknowledge the place and role of Christianity and the church in the history of Poland and the world.27

We find the same logic in the ‘Union Directions’ that had been announced in April, where the proclamation of the pluralist and open nature of the union is accompanied by the following declaration: ‘Christian inspiration was one of the fundamental ideological values that we include in our program. The crucifix hanging next to the Eagle, hanging in many union premises, is supposed to remind our members of their moral origin and to fill them with faith in the righteousness of our cause’.28 A certain rule can be gleaned here: submitting a postulate for pluralism was only possible after a prior recognition of the Christian foundations of the nation – and in this no contradiction was noticed. Behind it was the argument of the Catholic majority in Poland, as estimated both numerically and culturally, functioning as an omnipotent performative.

Mass during August strikes, Gdańsk Shipyard, 1980. Photographer unknown / collection of the European Solidarity Centre.

In this context, it is worth pointing out characteristic accents arising during the congress. It was preceded by a ‘Holy Mass to the intention of Solidarity celebrated by the new Primate of Poland, Archbishop Józef Glemp, in the Oliwa Cathedral in Gdańsk’.29 The first round of proceedings in the Olivia Hall was inaugurated by Lech Wałęsa with the Polish national anthem and Boże, coś Polskę [God Save Poland].30 ‘The second round of the congress began with Holy Mass, the singing of the anthem and of Boże, coś Polskę’.31 Masses accompanied each day of the proceedings.32 ‘The following days were opened by the subsequent homilies of Father Józef Tischner’,33 while sermons delivered on 6 and 27 September and on 5 October were included in official documents of the Congress.34 Here, the words of Bogdan Borusewicz recorded in Konspira [Conspiracy], published in 1984, sound credible.

I cannot imagine a situation in which a man would stand up during the elections for a Solidarity government and say: I am a non-believer. Among the candidates there were, after all, different people, Catholics and atheists, still everyone raised their crucifix up. There was no one who would say: I will not pledge this oath, because I am simply a non-believer – if you want, choose me, if not, don’t choose me.35

From the end of 1980, Father Tischner published essays in the magazine Tygodnik Powszechny36 which would then contribute to the volume Etyka solidarności [The Ethics of Solidarity]. That book opens and closes with homily texts37 from masses celebrated at Wawel Cathedral in Kraków. Tischner delivered the first to leading movement activists visiting Kraków (headed by Lech Wałęsa and Anna Walentynowicz), about which Jarosław Gowin succinctly commented: ‘It is difficult to give a more symbolic confirmation of the church’s influence on Solidarity’.38 Gowin emphasises that no one proposed a different code, nor did anyone question the description of the ethical experience of Solidarity that ‘was penned by a Catholic priest’.39 ‘If it was necessary to somehow define the meaning of the word “solidarity”, one would probably have to reach for the Gospel and look for its genealogy there’, wrote Tischner, the Solidarity chaplain, while emphasising that ‘The key to our cause is faith’.40 Sergiusz Kowalski sounds convincing while commenting on an argument for the syncretic character of Solidarity, namely that it was about a particular way of ‘reconciling matters’ based on the absorbing by the Catholic discourse of elements of the socialist one, as well as about accepting that which could be reconciled with the religious discourse – it was about an appropriate ‘preparation of threads’ and inscribing them into ‘the framework of the national-Catholic heritage’.41

The limits of pluralism

Sergiusz Kowalski, quoted above, is author of Krytyka solidarnościowego rozumu [A Critique of the Solidarity Mind-set], published in 1988. Its starting point is the colloquial opinion on Solidarity as a melting pot of various ideas, positions and beliefs, and its goal is to ‘detect a certain community of conceptual structures, a unity veiled by a multi-coloured curtain of union pluralism’.42

‘A Solidarity “we”, even though institutionalised, was [...] an area distinguished on the basis of axiological criteria with a moral aftertaste’,43 wrote Kowalski, thus stating the national character of the community shaped at the time and its ‘conservative traditionalism’.44 The content of the Solidarity utopia was drawn from history, while ‘building a new society is not an act of creation, but of reconstruction’, he wrote, emphasising the very frequent declaration of fidelity to tradition on the trade unionists’ part, which ‘conveys the timeless essence of the national community’.45 Asking about Solidarity as a ‘practical manifestation of ideology’, a locus of ‘hidden archetypes of collective thinking’,46 the author concluded that the first element of the collective bond (‘we’) was ‘the Catholic faith of the overwhelming majority of Polish society’,47 recognised as an immanent and essential component of the natural order and national tradition. This reasoning results from the adopted division into ‘us’ and ‘them’, where the Catholic identity ‘us’ becomes determined in opposition to the atheistic ‘they’, and the Catholic faith ‘following the example of the ancestors [is] nurtured in spite of the repressions on the part of the government favouring the alien (at one time Orthodox, today a Marxist-Leninist rite)’.48 Kowalski did not directly connect these two themes, but in this context it is a striking thesis that thinking about democracy as the will of the majority was characteristic for Solidarity, wherein the majority was granted ‘absolute authority’, ‘a practically sacred dimension that the views of minorities seem to be deprived of’: on this principle, ‘the rule of majority over minority constitutes an alternative to the former rule of minority over majority’.49

Kowalski’s diagnosis is particularly validated by the fact that he formulated it as early as in 1981 in Tygodnik Solidarność50 [Solidarity Weekly, 10 July issue]. Recalling the figure of a Catholic Pole in his text ‘Polski syndrom’ [‘The Polish Syndrome’] and mentioning ‘the dark pages of Polish Catholicism of the interwar period’, Kowalski wrote: ‘Today, old fears are coming back, as in front of our very eyes a new synthesis of the Catholic faith with the Polish cause is being made’. Solidarity is ‘a great national confederation, inevitably gravitating towards unity’, he wrote. Contrary to opinions about ‘the ecumenical spirit of dialogue and tolerance’ pervading the nation, he stated:

On the contrary, the general public seems to strive to eliminate all diversity, and instead of developing pluralism, it is ready to feed on the patriotic and Catholic symbol. Each idea and value, in order to gain recognition, must first receive the stamp of the church’s imprimatur. The lack of independent thinking, today ever more necessary, and of independent ideological search, and in particular the lack of courage to question the monopoly of faith and the church on the matter of Poland.[…] Therefore, I repeat: let’s defend ourselves and defend others against the new ideological totalism, against the return of the peremptory synthesis of ‘God’ and ‘Fatherland’, which shuts all intellectual horizons.51

Kowalski’s article was directly countered by a much longer text by Maciej Zięba, printed below it and opening with the statement: ‘Does the church endanger Solidarity? Contrary to journalistic principles, I will answer at the outset that I do not think so. I also think that millions of Poles share my opinion’.52 The discussion was cut short – and it was not continued in the magazine’s subsequent issues. Over its thirty-seven issues, there appeared not a single additional voice of this type, but in almost every one of those issues members of the church were provided space, through the reprinting of documents from the episcopate, sermons of Józef Tischner, letters of John Paul II and an interview with Józef Glemp. In the issue published after the death of Primate Wyszyński, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, the editor, wrote on the first page in the first paragraph: ‘We have lost someone who was a g e n e r a l l y recognised authority, whose voice was a measure to which e v e r y o n e had to respond; someone who more than anyone else personified the nation, its durability and dignity’.53 Dozens of regional committees, boards and Solidarity committees joined in the mourning on the magazine’s pages. Solidarity applied to have Wyszyński buried at Wawel Cathedral in Kraków, then came up with the initiative to erect a monument to the primate. In this context, Kowalski’s concerns that his text may violate ‘good tone’ sound meaningful – after all, he addresses issues that ‘cannot be written about’, and his words might be perceived as an ‘inappropriate flourish of militant atheism’.54

A similar example is provided by the Szczecin magazine Jedność [Unity], which appeared in official circulation in 1981 (as did Solidarity Weekly). In June 1981, Unity published in the Letters section a statement by Ryszard Kaszubowski, a ‘rank and file’ activist who criticised the ‘excessive religiousness’ of the trade union. While commenting on the 3 May ceremony and Solidarity’s banner with an image of the Virgin Mary and the inscription ‘God’, Kaszubowski asked:

Is the Solidarity union of [the district] West Pomerania a union for Catholics only? Do other union members feel well under this banner – non-believers, non-Catholics, Marxists? Would the Catholics gathered in Solidarity feel comfortable if their union banner included inscriptions and symbols of Lutherans, the Orthodox Church, Muhammad or Party symbols? What say you, decision-makers of our union? Have you by any chance accidently taken bad example from the people who imposed their ideas upon us and forced unanimity until August? Does it not sound like a lack of democracy?55

In response to Kaszubowski’s request for an answer, Unity reacted by printing two other letters, including one by Przemysław Fenrych and Jan Tarnowski, members of the Regional Board Presidium. The authors wrote, first, that ‘the cross is not a symbol of oppression for anyone’ and ‘can connect all people’; second, that ‘in our after all democratic union the decisive majority considers themselves Catholic and this majority decided […] that the banner should look like it does’. [Finally, the authors referred to the famous words of John Paul II, spoken during the mass inaugurating his first pilgrimage to Poland, celebrated in Warsaw’s Zbawiciela Square, in which the pope in turn referred to the millennium jubilee of Poland’s baptism exuberantly celebrated in 1966: ‘It is impossible to understand the history of the Polish nation – this great thousand-year-old community, which so profoundly represents me, each one of us – without Christ’.56 […] ‘A thousand years of the Polish nation is a thousand years of a Christian nation’, Fenrych and Tarnowski then wrote, ‘as John Paul II reminded us, and to which the strikers attested by hanging the image of Our Lady Queen of Poland on the gates of the industrial factories’.

Can one have a grudge against this belief? Can one deny the right to these symbols? Solidarity is not a Catholic union. But the majority of it is constituted by Catholics. And the values it wants to pursue derive from our old Polish culture and tradition. Let us not impoverish this tradition with ill-conceived tolerance and ‘consideration’ for our unbelieving brothers. After all, this ‘consideration’ cannot lead to the renunciation of one’s own convictions. Especially if these do not threaten anyone. ‘Leave your people alone’ and allow for not seeing a lack of democracy where there is no such thing.57

Characteristic of the rhetoric employed here is calling upon a representative of a minority to respect the rights of the majority, which is understood to be the principle of democracy. ‘[Y]ou could respect our feelings a little’, exhorted Karol Długosz, the author of the second letter, in the name of ‘ninety percent of the nation’.58 ‘We have received more letters presenting a similar position’, Unity declared, thereby cutting the discussion short.

‘The [P]roblem of the relationship between Solidarity and the church was not at all a subject of deeper reflection on the part of trade-union ideologues’,59 Antoni Dudek has argued. The voices just presented prove that such reflection was in fact present, however marginal. Both in the case of Solidarity Weekly and that of Unity, the admission of a dissenting voice was not made in the name of true pluralism, but rather as an alibi for pluralism as a postulate and declaration.[…]

Sergiusz Kowalski expanded his analysis from 1988 with an important argument. ‘Let us note, in the margins’, he wrote on Solidarity, ‘that pluralism is not created [here] out of love for pluralism’, and the manifestation of tolerance for minorities is something ‘safe and cost-free’, since ‘minorities are few in numbers (where they occur in larger communities, there has been, as we know, trouble)’. Kowalski recalls Leszek Kołakowski’s opinion on the Rijnsburg movement as a ‘certain analogy’ for the Solidarity movement: ‘they simply do not have the opportunity to practice tolerance, understood as refraining from repression of views contrary to their own’.60 It must borne in mind that Poland after the Second World War, then again later, after 1968, became largely a cultural and ethnic monolith – against which Aleksander Hertz wanted to caution at the Congress of Polish Culture in 1981. ‘Today’s Poland is ethnically uniform. It is far from the national or ethnically cultural pluralism of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. So-called minorities are preserved in rudimentary forms and are disappearing. I am anxiously thinking that this purity; this monolith carries a great danger for the future’.61 Pluralism, as evidenced, can have different horizons, and the Polish one is extremely limited.62

The logic of performance

Jan Sowa does not completely pass over the Catholic character of Solidarity (‘symbols and religious rituals are an important element of its functioning’63); however, he does state that the strikers had an ‘instrumental’ and ‘pragmatic’ attitude towards Christian symbolism: ‘what counted for them was the use they could make of the elements of the symbolic landscape surrounding them’.64 Faced with the sight of thousands of praying and confessing workers, it is difficult to defend this thesis – it can actually be easily overturned by recalling the history of the construction of the monument commemorating the events of December 1970, called for from the very first days of the strike. The Monument to the Fallen Shipyard Workers of 1970, near Gate No. 2 of the Gdańsk Shipyard, was unveiled on 16 December 1980. The ceremony was accompanied by a mass that was watched by all of Poland. The monument can be regarded as a symbolic culmination of the connection between the Romantic-era element65 and the Christian and national ones: it depicts three crosses topped with anchors (‘In Polish national symbolism for thousands of years, the cross has always been a symbol of faith and martyrdom, with the anchor as a symbol of hope’,66 we read in one of the first news items about the monument), that according to the final project were to be forty-four metres67 high (in the end, they measure forty-two meters, as this was the reach of the available crane68). The historical order was superseded by the mythical (Christian) order, best illustrated by the fact that, according to the initial design of Bohdan Pietruszka, the monument was to consist not of three but of four crosses, where the ‘number four symbolises the first fallen shipyard workers in December 1970’.69 The Christian order, in turn, was fixed in the institutional one: representatives of the church, headed by Primate Wyszyński, insisted on ‘abandoning the idea of the four crosses, as the Christian tradition suggests three’.70 It was not people who used symbols, one might say, but symbols (in the hands of an institution) that made use of people.

Unveiling of the Monument to the Fallen Shipyard Workers by Gate No 2, Gdańsk Shipyard. Photo: Zenon Mirota / collection of the European Solidarity Centre.

‘The claim that John Paul II overthrew communism is [...] untrue’, writes Sowa, while ‘interpretations regarding the causative role of the Catholic Church are definitely exaggerated’.71 I will pass over the controversial nature of this thesis. The simplification made here is based on limiting the understanding of the dynamics of social life to the order of historical facts, while at the same time neglecting the phantasmatic reality.72 As it would be naive to say that the use of Catholic symbols was only an act of political calculation, it is impossible to accept that it was an innocent practise. The point is that, as Bronisław Baczko wrote, presenting an extensive catalogue of national and religious celebrations between August 1980 and December 1981, ‘the updating of the past through images and symbols that refer to it allows us to confirm the values considered to be the most important for national identity and culture’, and in this case, ‘above all, Christian and Catholic values’.73 The question is therefore about the performative sense of those practices, of Solidarity as a cultural identity performance.

One must bear in mind that the perception of the past and the symbols used in Solidarity discourse were of fundamental importance in the struggle for the shape of collective memory, alternative to its institutional version promoted by the institutions of Communist-era Poland. The discourses of the church and the broadly understood opposition intersect here in common recognition of the role of religion in this counter-history (and even in religion itself as counter-history), conceptualised as a ‘mythic-religious’ history, the history of ‘hidden knowledge that must be discovered and deciphered’,74 and at the same time – contrary to Michel Foucault’s original definition – as a history of continuity (‘It is impossible to understand the history of the Polish nation […] without Christ’), legitimated in the social and cultural majority (‘ninety per cent’). The nation was constituted here as an imaginary community, with Christianity as a foundation – understood as a legitimation for the nation (‘us’) and used as a tool for delegitimising the power of Communists (‘them’). In the emotionally marked discourse of collective memory, the question of whether religion was understood as an inseparable component of Polish identity or as a set of universal values was ultimately of secondary importance. One could risk the claim that the differences indeed reported had no right to exist: for collective memory it is characteristic, after all, ‘to remove from it everything that disturbs the clarity of the black and white image’. The social bond, understood as a ‘psychic bond’ based on the ‘worship of shared values’, works as a result ‘in favour of giving the community the character of an ideological group’.75 This process became extremely intense after the imposition of martial law on 13 December 1981, yet grew in the field of previously shaped national phantasms and notions of the community about itself.

The order of real politics thus found legitimation in the alternative (to the Communist), national-Catholic symbolic universe – this is important for understanding Solidarity as a cultural performance. As Krzysztof Nowak argued in 1988, civil-society institutions germinating in Solidarity soon turned out to be ‘dramatically’ weak in confrontation with the overwhelming force of tradition and national and religious symbolism which provide ready patterns of behaviour and their legitimacy’.76 After all, it cannot be forgotten, as Ewa Domańska wrote, that counter-history is usually authoritarian: it contains an option of identity and politics, and at a convenient time can become official history.77 I will show this process in two examples.

Tygodnik Mazowsze [Mazovia Weekly], a semi-official publication of the Temporary Coordination Committee of the SolidarityIndependent Self-governing Labour Union78 – ‘the most serious magazine of underground Solidarity’79 – as part of a broad campaign to boycott Poland-wide elections to national councils in 1984, recalled, along with appeals of Solidarity and opposition leaders [...],‘Orędzie Episkopatu Polski w sprawie wyborów do sejmu’ [‘Address of the Polish Episcopate Regarding Elections to the Sejm’] from 1946: ‘Catholics can only vote for such persons, letters and electoral programs that do not contradict Catholic science and morality’.80 When before the 1991 elections the Episcopate argued that only those political groups that ‘show in their activities a concern for Poland and respect for its traditions stemming from its Christian roots should receive a mandate to legislate from believers’,81 it happened to the indignation of a part of the opposition. Meanwhile, after 1989, Christian values had been for the church a battlefield for the shape of the Third Polish Republic to a similar extent that those values – and the church itself – had been a locus of Solidarity’s struggle for its own legitimisation before 1989. The church used the historical card at least in the respect (and certainly in the same sense) in which the opposition had previously done so. What of it that the 1991 elections, contrary to those in 1984, were free and democratic. The understanding of democracy and the sense of historical order was tertiary to the understanding and feeling of the sense of the phantasmic order.

The second example is the fight for the presence of crucifixes in public places, workplaces and especially in schools – initiated by the hanging of a crucifix next to the Polish coat of arms at the conference room of the Gdańsk Shipyard during the August strikes, and later in the Olivia Hall during the programme conference. As Goniec Małopolski [The Małopolski Messenger] reported in May 1981:

Recently, crucifixes appeared in our schools – big and small, finely sculpted and crude, sometimes simply drawn in chalk on the wall. They appeared in various ways – officially, solemnly brought by parents and pupils, as if ‘introduced’ to school or – suddenly – unexpectedly hung in the afternoon and accepted the next day with silence, embarrassment or even disapproval. The fact is, however, that in the vast majority of schools there hang crucifixes, in auditoriums and classrooms, next to the national coat of arms.82

Hanging crucifixes in public places was, in the times of the first Solidarity movement, an element of (counter)historical policy, legitimising the new (national-Catholic) order. After 13 December 1981, the now-underground Solidarity made the struggle for crucifixes a part of a broad anti-Communist resistance movement. Mazovia Weekly, while reporting on its course,83 did not hesitate to quote a priest from Garwolin, who defended the presence of crucifixes in school classrooms with these words: ‘Poland has never been without a cross and it will stay with it forever’.84 The argument regarding the Catholic majority was used in this context by the bishops.85 It would be facetious to ignore the historical context of these events – the point is that a phantasm does not care for historical logic, always subject to interpretation. The boundary between history and myth, the law negotiated in the social order and the law grounded in the phantasmatic order, is blurred especially strongly in narratives anchored in national affect, in which collective memory and the legitimation of collective identity are at stake. An example of this is the fight over crucifixes, which was juxtaposed with the practice of Prussian Kulturkampf86 in the discourse of the opposition. Only a few years later, in 1991, the bishops reminded us of ‘the role that religion played in defending the rights of the nation, even in the time of the partitions or in the years of both world wars, and finally in the years of struggle against a totalitarian system that in principle negated God’ – thus arguing the need for the return of religious education to schools.87 ‘As a nation brought together by the baptism, as a nation with more than a thousand years of Christian culture, finally as a state that the church has served for centuries, we cannot relegate [...] this crucial matter to the margins’, wrote the bishops and, quoting John Paul II’s words uttered at the Zwycięstwa Square during his first pilgrimage and binding the history of man and nation with Christ, they decreed:

Many years ago a crowd of several thousand took up this call, answering with a song: We want God. In this song, as in organised life, there is a place for Christ ‘in the book, at school’. It corresponds with the spirit of the nation and therefore becomes our task.88

On 26 August 1993, on the day of the liturgical holiday of Our Lady of Czestochowa, during services at the Jasna Góra Monastery, a ‘Nowy Akt Zawierzenia Maryi Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej’ [‘New Act of Dedicating the Republic of Poland to the Virgin Mary’] was read, referring to the millennial ‘Akt Oddania Polski w macierzystą niewolę Maryi’ [‘Act of Dedication of Poland to the Maternal Captivity of the Virgin Mary’] from 1966. It was signed – at the altar – by Cardinals Józef Glemp, Franciszek Macharski and Henryk Gulbinowicz, President Lech Wałęsa, Prime Minister Hanna Suchocka and the Speakers of the Sejm, Wiesław Chrzanowski, and Senate, August Chełkowski.89

I propose to take a look at the thesis of Solidarity as ‘the most democratic place in the world’ from this perspective. Jan Sowa quotes it after Lawrence Goodwyn, who wanted to understand the logic of the cultural performance of Solidarity in a completely different way. In the 1980s, ‘the church became a refuge of Polishness and was to perform this role until an indefinite moment, so long awaited, when Poles would feel that they have regained control over their own fate’, wrote Goodwyn in 1991. ‘Presently it seems that the church can return to performing religious functions’.90

This article is excerpted from Marcin Kościelniak’s Egoiści. Trzecia droga w kulturze polskiej lat 80. [Egoists: A Third Way in Polish Culture of the 1980s] published in 2018 by the Zbigniew Raszewski Theatre Institute in Warsaw in the Nowa Biblioteka series.

Translated by Karolina Sofulak

WORKS CITED:

Anusz, Anna, Andrzej Anusz, Samotnie wśród wiernych. Kościół wobec przemian politycznych w Polsce (1944-1994) (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo ALFA, 1994)

Baczko, Bronisław, Wyobrażenia społeczne. Szkice o nadziei i pamięci zbiorowej, trans. by Małgorzata Kowalska (Warsaw: PWN, 1994)

Berndt, Ewa, ‘Krzyże w szkołach’, Goniec Małopolska 1981, no. 32

——‘Krzyże w szkołach chorzowskich, Wiadomości Katowickie 1981, no. 176

Bonowicz, Wojciech, ‘Słowa, których nie wolno zapomnieć’, in: Lekcja sierpnia. dziedzictwo ‘Solidarności’ po dwudziestu latach, ed. by Dariusz Gawin (Warsaw: IFiS PAN, 2002)

‘Deklaracja programowa w sprawie kultury narodowej, October 7, 1981’, in: I Krajowy Zjazd Delegatów NSZZ ‘Solidarność’. Stenogramy, ed. by Grzegorz Majchrzak, Jan Marek Owsiński, vol. 2 – II round, pt. 2 (Warsaw: Solidarity Archives Association, IPN, 2013)

‘Diariusz zjazdowy’, Tygodnik Solidarność 1981, no. 24

‘Diariusz zjazdowy’, Tygodnik Solidarność 1981, no. 25

Długosz, Karol [untitled], Jedność 1981, no. 26 (44)

Domańska, Ewa, Historie niekonwencjonalne. Refleksja o przeszłości w nowej humanistyce (Poznań: Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, 2006)

Dudek, Antoni, ‘Rewolucja robotnicza i ruch narodowowyzwoleńczy’, in: Lekcja sierpnia…, op. cit., p. 155

‘Dzisiaj Chrystus przemawia z Garwolina …’, Tygodnik Mazowsze 1984, no. 80/81

Fenrych, Przemysław, Jan Tarnowski, ‘W obronie sztandaru’, Jedność1981, no. 26 (44)

Fik, Marta, Autorytecie wróć? Szkice o postawach polskich intelektualistów po październiku 1956 (Warsaw: Errata, 1997)

Foucault, Michel, Trzeba bronić społeczeństwa. Wykłady w Collège de France, 1976, trans. by Małgorzata Kowalska (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo KR, 1998)

Friszke, Andrzej, Rewolucja Solidarności 1980–1981 (Kraków: Znak Horyzont, Instytut Studiów Politycznych PAN, European Solidarity Centre, 2014)

Garton Ash, Timothy, The Polish Revolution: Solidarity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002)

Goodwyn, Lawrence, Jak to zrobiliście? Powstanie Solidarności w Polsce, trans. by Katarzyna Rosner (Gdańsk: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, 1992)

Gowin, Jarosław, ‘Kościół a “Solidarność”’, in: Lekcja sierpnia. dziedzictwo ‘Solidarności’ po dwudziestu latach, ed. by Dariusz Gawin (Warsaw: IFiS PAN, 2002)

Hall, Aleksander, ‘List Aleksandra Halla do Tygodnika Mazowsze’, Tygodnik Mazowsze 1985, no. 126

Hellenowa, Józefa, ‘26 sierpnia na Jasnej Górze’ and ‘Jasnogórskie zawierzenie’, Tygodnik Powszechny 1993, no. 36

Hertz, Aleksander [untitled], in: Kongres Kultury Polskiej, op. cit., p. 105

‘A inne wyznania?’, Tygodnik Solidarność 1981, no. 30

Janion, Maria [untitled], in: Kongres Kultury Polskiej (Warsaw: Krąg, 1982)

Jędrychowska, Jagoda [Kazimiera Kijowska], Rozmowy kontrolowane (Poznań: Kantor Wydawniczy SAWW, 1990)

John Paul II, ‘Homilia w czasie Mszy św. odprawionej na placu Zwycięstwa 2 czerwca 1979’, in: Pielgrzymki do ojczyzny 1979, 1983, 1987, 1991, 1995, 1997, 1999, 2002. Przemówienia, homilie (Kraków: Znak, 2005)

Kaszubowski, Ryszard, ‘Związek i religia’, Jedność 1981, no. 24 (42)

‘Katolik a wybory’,Tygodnik Mazowsze 1984, no. 86

‘Kierunki działania Związku w obecnej sytuacji kraju’, Tygodnik Solidarność 1981, no. 3

Kijowski, Andrzej, ‘Co zmieniło się w świadomości polskiego intelektualisty po 13 grudnia 1981?’, Arka 1983, no. 4

Komunikat z 250. Konferencji Plenarnej Episkopatu Polski, 17 października 1991’, Pismo Okólne, no. 42/91/1232, 14–20 October 1991

Kowalski, Sergiusz, Krytyka solidarnościowego rozumu. Studium z socjologii myślenia potocznego (Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Akademickie i Profesjonalne, 1990)

——‘Polski syndrom’, Tygodnik Solidarność 1981, no. 15

‘Kronika ’93 (9)’, Jasna Góra1993, no. 11

Kto tu wpuścił dziennikarzy, concept by Marek Miller (Łódź, Warsaw: Pracownia Reportażu, Niezależna Oficyna Wydawnicza, c. 1984)

Kula, Marcin, Narodowe i rewolucyjne (London, Warsaw, Aneks, 1991)

‘Kulturkampf’, Kultura Niezależna 1984, no. 1

Listy Pasterskie Episkopatu Polski 1945–2000, pt. 2, ed. by Piotr Libera, Andrzej Rybicki, Sylwester Łącki (Marki: Michalineum, 2003)

Łopiński, Maciej, Marcin Moskit [Zbigniew Gach], Mariusz Wilk, Konspira. Rzecz o podziemnej Solidarności (Paris: Editions Spotkania, 1985)

Mazowiecki, Tadeusz [untitled], Tygonik Solidarność 1981, no. 10

Michałko, Jacek, ‘Solidarność a Kościół’, AS. Biuletyn Pism Związkowych i Zakładowych 1981, no. 16

Michnik, Adam, Takie czasy… (Warsaw: Agora, 2009)

——Józef Tischner, Jacek Żakowski, Między panem a plebanem (Kraków: Znak, 1995)

‘Modlitwa zawierzenia Kościoła w Polsce’, Jasna Góra 1993, no. 10

Niepokora. Artyści i naukowcy dla Solidarności 1980–1990, ed. by Stefan Figlarowicz, Katarzyna Goc, Grażyna Goszczyńska, Anna Makowska, Anna Szynwelska (Gdańsk: słowo/obraz terytoria, National Museum in Gdańsk, 2006)

Niesiołowski, Stefan, ‘Lewica laicka i narodowa demokracja’,Solidarność Ziemi Łódzkiej 1981, no. 36 (49)

Nowak, Krzysztof, ‘Dekompozycja i rekompozycja działań zbiorowych a przemiany systemu dominacji: Polska lat osiemdziesiątych’, in: Społeczeństwo polskie u progu przemian, ed. by Janusz Mucha, Grażyna Skąpska, Jacek Szmatka, Izabella Uhl (Wrocław: Ossolineum, 1991)

‘Obchody 1 i 3 maja’, AS. Biuletyn Pism Związkowych i Zakładowych 1981, no. 13

‘Orędzie Episkopatu Polski w sprawie wyborów do sejmu, 10 września 1946’, in: Listy pasterskie Episkopatu Polski 1945–1974 (Paris: Éditions du Dialogue, 1975)

‘Polish Workers Move’, Workers Vanguard, no. 263, 5 September 1980

‘Pomnik Stoczniowców Poległych w 1970’, Strajkowy Biuletyn Informacyjny Solidarność, no. 4, 25 August 1980

Popiełuszko, Jerzy, Kazania patriotyczne (Paris: Libella, 1984)

‘Pytania i odpowiedzi’, Niezależność 1980, no. 4, unpag.

Raina, Peter, Kościół w PRL. Kościół katolicki a państwo w świetle dokumentów 1945–1989, vol. 3 (Poznań, Pelpin: W Drodze, Bernardinum, 1996)

W rocznicę Grudnia, Polska Kronika Filmowa1980/52a

Rojek, Paweł, Semiotyka Solidarności. Analiza dyskursów PZPR i NSZZ Solidarność 1981 roku (Kraków: Nomos, 2009)

‘Rozsądni’, Przegląd 1980, no. 6

‘Sierpniowe refleksje’, Bratniak 1980, no. 25

Solidarność a polityka antypolityki, trans. by Sergiusz Kowalski (Gdańsk: European Solidarity Centre, 2014)

Solidarność w ruchu 1980–1981, ed. by Marcin Kula (Warsaw: Niezależna Oficyna Wydawnicza NOWA, 2000)

Sowa, Jan, Inna Rzeczpospolita jest możliwa! Widma przeszłości, wizje przyszłości (Warsaw: Grupa Wydawnicza Foksal, 2015)

Staniszkis, Jadwiga, A Self-limiting Revolution, ed. by Jan T. Gross, transl. by Marek Szopski (Gdańsk: European Solidarity Centre, 2010)

Susuł, Jacek, ‘Gdańsk, 16 grudnia 1980’, Tygodnik Powszechny 1981, no. 2

Świerczyński, Czesław, ‘Dla nauczycieli, Wiadomości Katowickie1981, no. 145

Szacka, Barbara, Czas przeszły – pamięć – mit (Warsaw: Instytut Studiów Politycznych PAN, Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar, 2006–2007)

Szacki, Jerzy, Liberalizm po komunizmie (Kraków, Warsaw: Znak, Stefan Batory Foundation, 1994)

Tischner, Józef, Etyka solidarności (Kraków: Znak, 1981)

‘TM – wywiad z samym sobą’, Tygodnik Mazowsze 1984, no. 100

Tygodnik Mazowsze 1984, nos. 75/76, 80/81, 82; 1985, nos. 111, 115, 129, 134

‘Uchwała programowa I Krajowego Zjazdu Delegatów NSZZ “Solidarność”’ in: I Krajowy Zjazd Delegatów NSZZ ‘Solidarność’. Stenogramy, ed. by Grzegorz Majchrzak, Jan Marek Owsiński, vol. 1 – I round (Warsaw: Solidarity Archives Association, IPN, 2011)

Wyszyński, Stefan, ‘Mamy widzieć przed sobą cały Naród (do przedstawicieli NSZZ “Solidarność”) 10 November 1980’, in: Kościół w służbie Narodu. Nauczanie prymasa Polski czasu odnowy w Polsce, sierpień 1980 – maj 1981 (Rome: ‘Corda Cordi’, Delegation of the Press Office of the Polish Episcopate, 1981)

‘Zawierzenie całej Polski’, Gazeta Wyborcza, 27 August 1993

Zięba, Maciej, ‘Czy Kościół zagraża “Solidarności”?’, Tygodnik Solidarność 1981, no. 15

1. Jerzy Szacki, Liberalizm po komunizmie (Kraków, Warsaw: Znak, Stefan Batory Foundation, 1994), pp. 140–141.

2. Paweł Rojek, Semiotyka Solidarności. Analiza dyskursów PZPR i NSZZ Solidarność 1981 roku (Kraków: Nomos, 2009), p. 11.

3. Ibidem.

4. Jan Sowa, Inna Rzeczpospolita jest możliwa! Widma przeszłości, wizje przyszłości (Warsaw: Grupa Wydawnicza Foksal, 2015), p. 147.

5. Ibidem. p. 148.

6. Ibidem, p. 141.

7. Marcin Kula, Narodowe i rewolucyjne (London, Warsaw, Aneks, 1991), pp. 281, 293, 273.

8. I have borrowed the terms from: Adam Michnik, Takie czasy… (Warsaw: Agora, 2009), pp. 143–144; Jadwiga Staniszkis, A Self-limiting Revolution, ed. by Jan T. Gross, trans. by Marek Szopski (Gdańsk: European Solidarity Centre, 2010), p. 167; Solidarność w ruchu 1980–1981, ed. by Marcin Kula (Warsaw: Niezależna Oficyna Wydawnicza NOWA, 2000), p. 195; Jerzy Popiełuszko, Kazania patriotyczne (Paris: Libella, 1984), p. 193.

9. As cited in: ‘Pytania i odpowiedzi’, Niezależność 1980, no. 4, unpag.

10. Timothy Garton Ash, The Polish Revolution: Solidarity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), p. 45.

11. Kto tu wpuścił dziennikarzy, concept by Marek Miller (Łódź, Warsaw: Pracownia Reportażu, Niezależna Oficyna Wydawnicza, c. 1984), pp. 93–94.

12. Andrzej Kijowski, ‘Co zmieniło się w świadomości polskiego intelektualisty po 13 grudnia 1981?’, Arka 1983, no. 4, pp. 9–10.

13. As cited in: ‘Rozsądni’, Przegląd 1980, no. 6, p. 31.

14. Protests of Polish workers violently suppressed by militia and armed forces (including in Gdańsk, Gdynia, Szczecin) from 14 to 22 December 1970.

15. At the time of May holidays, the Solidarity bulletin reported: Bydgoszcz: ‘laying wreaths at the monument of martyrdom, solemn mass’; Katowice: ‘a pilgrimage to the sacred Franciscan site in Panewniki, Holy Mass at the monument of Silesian Insurgents’; Krosno: ‘Holy Mass, consecration of the banner of the regional trade-union organization, march through the city with a missionary cross and erecting it next to the St. Spirit Church’; Gdańsk: ‘after the Holy Mass at the Virgin Mary Basilica in the Old Town, a rally of Tri-City people took place’; Warsaw: ‘A Pontifical Holy Mass was celebrated at St. John’s Cathedral. The Solidarity delegation laid flowers by the original copy of the Constitution of May 3’; Tychy: ‘a rally organized by the Inter-enterprise Founding Committee [MKZ] culminating in a Holy Mass’; Kędzierzyn-Koźle: ‘a religious-patriotic rally, preceded by ringing bells throughout the city; in the program: a field mass, consecration of the banner, a history lecture’; Grudziądz: ‘MKZ along with with KM SD organized a field mass at the central stadium’; Krosno: ‘A Holy Mass celebrated by Bishop I. Tokarczuk, consecration of the regional organisation banner’; Opole: ‘a rally at the amphitheatre, Holy Mass, occasional lectures’; Kraków: ‘Mass at Wawel Cathedral’, placing flowers at Tadeusz Kościuszko’s plaque’; Szczecin: ‘consecration of the banner of the Solidarity Independent Self-governing Labour Unionfor West Pomerania’ (as cited in: ‘Obchody 1 i 3 maja’, AS. Biuletyn Pism Związkowych i Zakładowych 1981, no. 13, p. 212; no. 14, p. 211).

16. The iconic image of Our Lady of Czestochowa, at the shrine to the Virgin Mary at the Jasna Góra Monastery in Częstochowa, Poland, is revered by a religious and national cult as a symbol of Polish Catholicism.

17. Jacek Susuł, ‘Gdańsk, 16 grudnia 1980’, Tygodnik Powszechny 1981, no. 2, p. 6.See: W rocznicę Grudnia, Polska Kronika Filmowa 1980/52a, http://www.kronikarp.pl/szukaj,11828,tag-689931.

18. One might ignore this, as did David Ost, writing: ‘The relations of the Church with Solidarity were complicated, controversial and beyond the scope of this work’. Such omission is costly, however: it leads that author not only to state that Solidarity was leftist, but also that it was ‘postmodern left-wing’. See Ost,Solidarność a polityka antypolityki, trans. by Sergiusz Kowalski (Gdańsk: European Solidarity Centre, 2014), pp. 41–42, 239).

19. Sierpniowe refleksje, Bratniak 1980, no. 25, p. 6.

20. Jacek Michałko, ‘Solidarność a Kościół’, AS. Biuletyn Pism Związkowych i Zakładowych 1981, no. 16, p. 501.

21. ‘Polish Workers Move’, Workers Vanguard, no. 263, 5 September1980, p. 1.

22. The Congress of Polish Culture in 1981 was convened by the Creative and Scientific Associations Conciliatory Committee on the surge of social and political ferment from Solidarity. The congress, planned for 11–13 December 1981, was interrupted by the introduction of martial law on 13 December.

23. Maria Janion [untitled], in: Kongress Kultury Polskiej (Warsaw: Krąg, 1982), pp. 22, 18.

24. Stefan Wyszyński, ‘Mamy widzieć przed sobą cały Naród (do przedstawicieli NSZZ “Solidarność”) 10 November 1980’, in: Kościół w służbie Narodu. Nauczanie prymasa Polski czasu odnowy w Polsce, sierpień 1980 – maj 1981 (Rome: ‘Corda Cordi’, Delegation of the Press Office of the Polish Episcopate, 1981), pp. 106–107.

25. The First National Congress of Delegates of the Solidarity Independent Self-governing Labour Union, held on 5–10 September and on 26 September – 7 October 1981, was a key events of Solidarity’s legal period.

26. ‘Uchwała programowa I Krajowego Zjazdu Delegatów NSZZ “Solidarność”’ in: I Krajowy Zjazd Delegatów NSZZ ‘Solidarność’. Stenogramy, ed. by Grzegorz Majchrzak, Jan Marek Owsiński, vol. 1 – I round (Warsaw: Solidarity Archives Association, IPN, 2011), p. 984.

27. ‘Deklaracja programowa w sprawie kultury narodowej, October 7, 1981’, in: I Krajowy Zjazd Delegatów NSZZ ‘Solidarność’. Stenogramy, ed. by Grzegorz Majchrzak, Jan Marek Owsiński, vol. 2 – II round, pt. 2 (Warsaw: Solidarity Archives Association, IPN, 2013), p. 930.

28. ‘Kierunki działania Związku w obecnej sytuacji kraju’, Tygodnik Solidarność 1981 no. 3, p. 2.

29. ‘Diariusz zjazdowy’, Tygodnik Solidarność 1981, no. 24, p. 1.

30. A nineteenth-century Polish Catholic religious song, with nearly the status of the national anthem, expressing aspirations of independence and associating patriotic attitudes with attachment to the Catholic God.

31. Andrzej Friszke, Rewolucja Solidarnośći 1980–1981 (Kraków: Znak Horyzont, Instytut Studiów Politycznych PAN, European Solidarity Centre, 2014), p. 661.

32. ‘From the second day of the sessions (Sunday 6 September) a Holy Mass will be celebrated in the Olivia Hall at 8 AM for the Congress participants’; ‘Diariusz zjazdowy’, Tygodnik Solidarność 1981, no. 25, p. 1.

33. Andrzej Friszke, Rewolucja Solidarnośći 1980–1981, op. cit., p. 576.

34. See: I Krajowy Zjazd…, vol. 1 – I round, op. cit., p. 1040; I Krajowy Zjazd…, vol. 2 – II round, pt. 2, op. cit., pp. 897, 916.

35. Maciej Łopiński, Marcin Moskit [Zbigniew Gach], Mariusz Wilk, Konspira. Rzecz o podziemnej Solidarności (Paris: Editions Spotkania, 1985), p. 14.

36. A Catholic social and cultural magazine, published from 1945 (with breaks). During Communist-era Poland it held the status of the most important independent magazine, representing the worldview of the so-called open and ecumenical church and the liberal current of Polish Catholicism.

37.‘Also some other chapters of Etyka… (for example “Gospodarstwo”) had their prototype in homilies’; Wojciech Bonowicz, ‘Słowa, których nie wolno zapomnieć’, in: Lekcja sierpnia. dziedzictwo ‘Solidarności’ po dwdziestu latach, ed. by Dariusz Gawin (Warsaw: IFiS PAN, 2002), p. 65.

38. Jarosław Gowin, ‘Kościół a “Solidarność”’ in: Lekcja sierpnia…, op. cit., p. 29.

39. Ibidem.

40. Józef Tischner, Etyka solidarności (Kraków: Znak, 1981), pp. 6, 8. It is difficult to consider the nature of this proposal as ‘inclusive’, as Gowin wants (Jarosław Gowin, ‘Kościół a “Solidarność”’, op. cit., p. 31).

41. Sergiusz Kowalski, Krytyka solidarnościowego rozumu. Studium z socjologii myślenia potocznego (Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Akademickie i Profesjonalne, 1990), pp. 116, 59. Years later, Adam Michnik recalled the first full edition of another book by Tischner, Polski kształt dialogu (appearing in autumn 1981, precisely at the time of publication of Etyka Solidarności) and accused Tischner of negating the path and achievements of the formation of the lay Left. ‘There was church triumphalism there combined with a complete absence of critical self-reflection’, leading to the conclusion that ‘you cannot be a Pole if you have not knelt before the Black Madonna’. ‘[A]t that time I did not call for it. I wanted to broaden the experiences and viewpoints’, Tischner replied to Michnik, adding that ‘Today I think you are right’ (Adam Michnik, Józef Tischner, Jacek Żakowski, Między panem a plebanem (Kraków: Znak, 1995), p. 347). After 1989, Tischner did not agree to the re-issuing of the book, which only happened after his death.

42. Sergiusz Kowalski, Krytyka solidarnościowego rozumu…, op. cit., p. 21.

43. Ibidem, p. 143.

44. Ibidem, p. 119.

45. Ibidem, pp. 112–113.

46. Ibidem, p. 28.

47. Ibidem, p. 118.

48. Ibidem.

49. Ibidem., p. 129.

50. The first Solidarity magazine to appear in official national circulation. Thirty-seven issues appeared, up to the imposition of martial law (the first on 13 April 1981). Tadeusz Mazowiecki was editor-in-chief.

51. Sergiusz Kowalski, ‘Polski syndrom’, Tygodnik Solidarność 1981, no. 15, pp. 4–5.

52. Maciej Zięba, ‘Czy Kościół zagraża “Solidarności”?’, Tygodnik Solidarność 1981, no. 15, pp. 4–5. Zięba’s reference is to a Paris Match survey conducted in Poland.

53. Tadeusz Mazowiecki, untitled, Tygonik Solidarność 1981, no. 10, p. 1.

54. It must be borne in mind that Solidarity Weekly represented the ‘liberal’ wing of Solidarity. Stefan Niesiołowski in Solidarność Ziemi Łódzkiej in a text with the telling title that translates as ‘The Lay Left-wing and National Democracy’,complained that he had to refuse to run his answer to Kowalski’s article in Tygodnik Solidarność, as it would have been abbreviated (‘Our union is for everyone, but the weekly Solidarity is not for opponents: Kowalski, Michnik, Blumsztajn, et consortes’). While Tygodnik Solidarność cut the discussion short, arguing that Kowalski was wrong, Niesiołowski insisted that Kowalski was indeed right, but was wrong only in assessing the phenomena he described. ‘Most threats mentioned by S.K. are to me evidence of a correct process, manifestations of the nation’s recovery of its rights, these are sources of joy and hope’, he wrote (Stefan Niesiołowski, ‘Lewica laicka i narodowa demokracja’,Solidarność Ziemi Łódzkiej 1981, no. 36 (49), pp. 2, 3).

55. Ryszard Kaszubowski, ‘Związek i religia’, Jedność 1981, no. 24 (42), p. 8.

56. ‘If we rejected this key to understanding our nation, we would be exposed to a fundamental misunderstanding. We would not understand ourselves’; John Paul II, ‘Homilia w czasie Mszy św. odprawionej na placu Zwycięstwa on 2 June 1979’, in: idem, Pielgrzymki do ojczyzny 1979, 1983, 1987, 1991, 1995, 1997, 1999, 2002. Przemówienia, homilie (Kraków: Znak, 2005), p. 23.

57. Przemysław Fenrych, Jan Tarnowski, ‘W obronie sztandaru’, Jedność 1981, no. 26 (44), p. 8.

58. Karol Długosz, untitled, Jedność 1981, no. 26 (44), p. 8. Długosz expanded the list of Fenrych and Tarnawski’s arguments with his own about the church’s role in the survival of the nation and the assurance that ‘Poland will never be Turkey’.

59. Antoni Dudek, ‘Rewolucja robotnicza i ruch narodowowyszwoleńczy’, in: Lekcja sierpnia…, op. cit., p. 155.

60. Sergiusz Kowalski, Krytyka solidarnościowego rozumu…, op. cit., p. 149.

61. Aleksander Hertz, untitled, in: Kongres Kultury Polskiej, op. cit., p. 105. His paper, planned for the third day of the congress, 13 December 1981, was not delivered [martial law ended the proceedings] – it was reprinted in the annex to the cited publication.

62. This thesis may be confirmed by an editorial letter in the Evangelical periodical Jednota, reprinted in the announcements section of Tygodnik Solidarność, ‘A inne wyznania?’. The letter points out that in negotiations with the government on accessibility to the media – one of the postulates and achievements of August [1980] – representatives of other faiths, including other Christian ones, were omitted and the conversations were monopolised by the Catholic Church. ‘Democracy is a wonderful but difficult and sometimes uncomfortable thing, especially when it has to be used in the practical life of societies. We are all citizens of the same country, children of the same homeland, and we all have the same rights. The issue concerns purely respecting these rights also with regard to groups and environments behind which there stands no multi-million crowd and its power’ (‘A inne wyznania?’, Tygodnik Solidarność 1981, no. 30, p. 16). The rhetoric of Christian values adopted as universal in Solidarity was, as is evidenced, a hypostasis, if not hypocrisy, to paraphrase Marta Fik. See: Marta Fik, Autorytecie wróc? Szkice o postawach polskich intelektualistów po październiku 1956 (Warsaw: Errata, 1997), p. 202.

63. Jan Sowa, Inna Rzeczpospolita…, op. cit., p. 139.

64. Ibidem, p. 147.

65. In Polish Romanticism, problems connected with the loss of Poland’s independence as a result of partitions were strongly present. Maria Janion spoke about this Romantic paradigm that has been in force for two centuries in the system of Polish culture, organised around values such as fatherland, independence, freedom of the nation and national solidarity, while recognising Solidarity as one of the culminations of this Romantic paradigm.

66. ‘Pomnik Stoczniowców Poległych w 1970’, Strajkowy Biuletyn Informacyjny Solidarność, no. 4, 25 August 1980, p. 1.

67. The height was to be symbolic: in the third part of the dramatic poem Dziady by Adam Mickiewicz, among the crucial works of Polish literature, the number ‘forty and four’ appears as the name of the future redeemer of the nation. Now a figure of Polish Romantic messianism, widely recognised in Poland.

68. As reported by Grzegorz Boros and Wiesław Szyślak in: Niepokora. Artyści i naukowcy dla Solidarności 1980–1990, ed. by Stefan Figlarowicz, Katarzyna Goc, Grażyna Goszczyńska, Anna Makowska, Anna Szynwelska (Gdańsk: słowo/obraz terytoria, National Museum in Gdańsk, 2006), pp. 29, 121.

69. Andrzej Perzyński, Waldemar Rebinin, Józef Widerlik, Kazimierz Zastawny; as cited in: ‘Pomnik Stoczniowców Poległych w 1970’, op. cit.

70. Anna and Andrzej Anusz, Samotnie wśród wiernych. Kościół wobec przemian politycznych w Polsce (1944-1994) (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo ALFA, 1994), p. 133.

71. Jan Sowa, Inna Rzeczpospolita…, op. cit., pp. 145, 147.

72. Andrzej Kijowski argued in 1982 that the power of Solidarity stemmed from the fact that it expressed itself ‘in the style corresponding to the Polish majority’: ‘If the strike movement expressed, for instance, leftist, revolutionary rhetoric [...] it would not have achieved such social resonance as it did by expressing itself with Catholic symbolism, Catholic ritual and Catholic aura. If portraits of Ignacy Daszyński or even Józef Piłsudski were hung on the shipyard’s gates, they would not have attracted such crowds that would not have surrounded them with prayer and rapture as when the paintings of Our Lady of Częstochowa and Pope John Paul II hung on these gates’. See: Jagoda Jędrychowska [Kazimiera Kijowska], Rozmowy kontrolowane (Poznań: Kantor Wydawniczy SAWW, 1990), pp. 35–36.

73. Bronisław Baczko, Bronisław Baczko, Wyobrażenia społeczne. Szkice o nadziei i pamięci zbiorowej, trans. by Małgorzata Kowalska (Warsaw: PWN, 1994), p. 238.

74. Michel Foucault, Trzeba bronić społeczeństwa. Wykłady w Collège de France, 1976, trans. by Małgorzata Kowalska (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo KR, 1998), pp. 77, 79.

75. Barbara Szacka, Czas przeszły – pamięć – mit (Warsaw: Instytut Studiów Politycznych PAN, Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar, 2006–2007), p. 50.

76. Krzysztof Nowak, ‘Dekompozycja i rekompozycja działań zbiorowych a przemiany systemu dominacji: Polska lat osiemdziesiątych’, in: Społeczeństwo polskie u progu przemian, ed. by Janusz Mucha, Grażyna Skąpska, Jacek Szmatka, Izabella Uhl (Wrocław: Ossolineum, 1991), p. 167.

77. See: Ewa Domańska, Historie niekonwencjonalne. Refleksja o przeszłości w nowej humanistyce (Poznań: Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, 2006), pp. 53–59. Domańska rightly reminds critical researchers about this thesis.

78. ‘TM – wywiad z samym sobą’, Tygodnik Mazowsze 1984, no. 100, p. 1.

79. Aleksander Hall, ‘List Aleksandra Halla do Tygodnika Mazowsze’, Tygodnik Mazowsze 1985, no. 126, p. 2.

80. ‘Katolik a wybory’,Tygodnik Mazowsze 1984, no. 86, p. 4. See: ‘Orędzie Episkopatu Polski w sprawie wyborów do sejmu, 10 września 1946’, in: Listy pasterskie Episkopatu Polski 1945–1974 (Paris: Éditions du Dialogue, 1975), p. 42.

81. Komunikat z 250. Konferencji Plenarnej Episkopatu Polski, 17 października 1991’, Pismo Okólne, no. 42/91/1232, 14–20 October 1991, p. 2.

82. Ewa Berndt, ‘Krzyże w szkołach’, Goniec Małopolska 1981, no. 32, p. 14. See also: ‘Krzyże w szkołach chorzowskich, Wiadomości Katowickie 1981, no. 176, p. 2; Czesław Świerczyński, ‘Dla nauczycieli, Wiadomości Katowickie 1981, no. 145, p. 2.

83. See: Tygodnik Mazowsze1984, nos. 75/76, 80/81, 82; 1985, nos. 111, 115, 129, 134.

84. ‘Dzisiaj Chrystus przemawia z Garwolina…’ Tygodnik Mazowsze 1984, no. 80/81, p. 4.

85. In March 1986, the Kielce bishops protested: ‘Schools are the property of the entire nation, in the vast majority a believing one that maintains these schools with great difficulty’. Two years earlier, Jan Mazur, the bishop of Siedlce, commented on the decisions of the state authorities to remove crucifixes as ‘disregarding the will of the vast majority of the believing Polish nation, and therefore undemocratic’. In Peter Raina, Kościół w PRL. Kościół katolicki a państwo w świetle dokumentów 1945–1989, vol. 3 (Poznań, Pelpin: W Drodze, Bernardinum, 1996), pp. 532, 424.

86. See: ‘Kulturkampf’, Kultura Niezależna 1984, no. 1, pp. 83–85. The article was published anonymously in the Events section edited by Andrzej Kaczyński. In Polish territories under Prussian rule, the practice of Kulturkampf was not only related to a policy aimed at limiting the influence of the Catholic Church, but also with the intensification of Germanic policy aimed at Polish culture.

87. Requiring religious education to state schools was one of the key political goals of the church after the fall of Communism. The introduction took place in 1990, and it took place by bypassing both the long statutory procedure and the parliament.

88. ‘List pasterski Episkopatu Polski w sprawie powrotu katechizacji do szkoły polskiej 16 czerwca 1990’, in: Listy Pasterskie Episkopatu Polski 1945-2000, pt. 2, ed. by Piotr Libera, Andrzej Rybicki, Sylwester Łącki (Marki: Michalineum, 2003), pp. 1649, 1653. The same argument returns, for instance, in.: ‘The Letter of the Polish Episcopate Regarding Catechesis from 22 June 1991’ (ibidem, p. 1710); ‘Słowo pasterskie biskupów polskich o zadaniach katolików wobec wyborów do parlamentu’ from26 August 1991 (ibidem, p. 1727).

89. See: ‘Modlitwa zawierzenia Kościoła w Polsce’, Jasna Góra 1993, no. 10 and ‘Kronika ’93 (9)’, Jasna Góra 1993, no. 11. See also: Józefa Hellenowa, ‘26 sierpnia na Jasnej Górze’ i ‘Jasnogórskie zawierzenie’, Tygodnik Powszechny 1993, no. 36, pp. 2, 13; ‘Zawierzenie całej Polski’, Gazeta Wyborcza, 27 August 1993 – in both cases, the coverage of an event did not include a polemical comment.

90. Lawrence Goodwyn, Jak to zrobiliście? Powstanie Solidarności w Polsce, trans. by Katarzyna Rosner (Gdańsk: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, 1992), p. 588.

Filled under:

Catholic Church; First Solidarity Movement; Polish Modernity; Trade Unions; Solidarity as a Performance