Theatre Collectives, Panel 1: How Do the Flemish Do It?

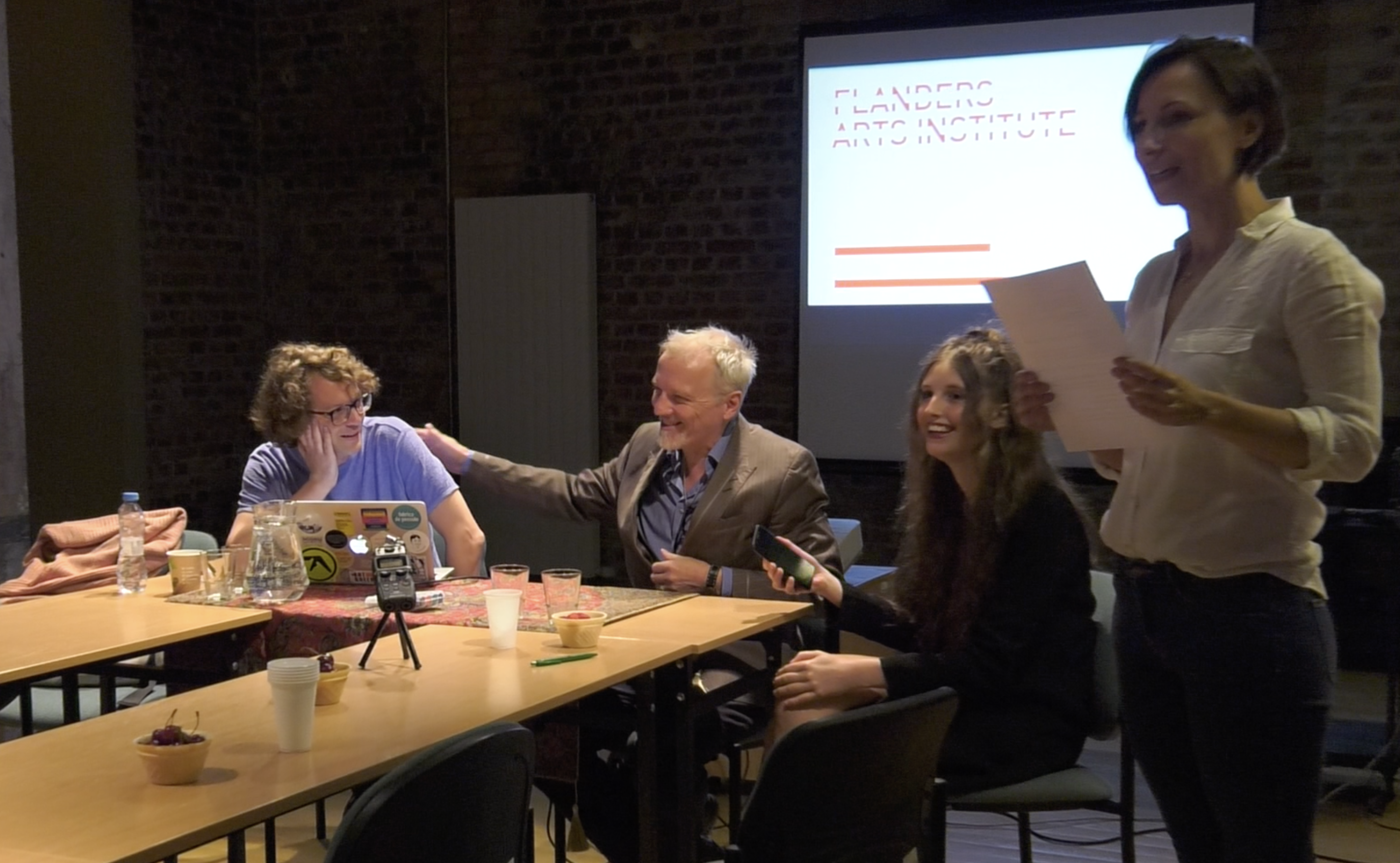

From left: Joris Janssens, Jan Lauwers, Lisaboa Houbrechts, Agata Siwiak, 'Theatre, Artistic and Research Collectives' conference, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, 19 June 2018. Photo from the recording by Anna Paprzycka.

The paper is a record of the panel discussion taking place as part of the conference 'Theatre, Artistic and Research Collectives', organised by the Institute of Theatre and Media Art (Faculty of Polish and Classical Philology, at the Adam Mickiewicz University) in cooperation with the Malta Festival, held on 19 June 2018 in Poznań. The main topic of the discussion concerned possible alternatives to the existing system of organising theatrical life in Europe. Participants discussed historical and contemporary Flemish artistic collectives and their ways of functioning. The conversation also included topics related to the forms of artists’ associations, the democratisation of production, funding and values generated by artistic collectives. Another important topic of the conversation was the situation of independent artists and the mechanism of institutional support for artists in the field of performing arts.

The pages to follow are a record of the first panel discussion held as part of the conference 'Theatre, Artistic and Research Collectives', organised by the Institute of Theatre and Media Art (Faculty of Polish and Classical Philology, at the Adam Mickiewicz University) in cooperation with the Malta Festival, on 19 June 2018 in Poznań. The panel guests included Jan Lauwers (Needcompany), Joris Janssens (the Flanders Arts Institute) and Lisaboa Houbrechts (Kuiperskaai). This record reflects the order of the meeting, which began with two guest presentations (by Janssens and Lauwers), followed by a discussion among Lisaboa Houbrechts, Johan Penson (Needcompany's general manager) and conference participants, invited to join the discussion. It excludes statements of an ordering nature by moderators Dr. Agata Siwiak and Katarzyna Tórz, and has been edited, annotated and shortened by Ewa Guderian-Czaplińska.

Presentation by Joris Janssens (Flanders Arts Institute):1

The ways in which artistic collectives function in Flanders could be presented in the form of several different models, some from the past, others from today. Collectives are of course established mainly for artistic reasons, but the possibilities of creating sustainable working conditions, solidarity and trust in an ever-changing environment are equally important. The 1980s looked completely different in this respect than today does, so it's a good idea to start this short review around that time. Firstly, because the Polish audience probably does not know this economic and organisational segment of the history of Flemish collectives, and secondly because many artists still active in the field of art began their work in the 1980s and contributed to the creation of this incredible boom that was later called the Flemish Wave.

And it was not easy to start, because there was no state policy to support performing arts (or contemporary art at all), and the budget dedicated to independent artistic projects was virtually non-existent. For example, in 1985, about nine per cent of the total amount of money allocated to culture was set aside for the 'dance' sector, but almost all of that amount went to the National Ballet team; of that nine per cent, only two per cent was then allocated for co-financing independent contemporary-dance companies and for the organisation of dance festivals, so the support was rather symbolic.

How did the artists deal with this? They began to associate. In the early 1980s, for example, the organisation Schaamte vzw (which can be translated as Shame npro), which started as a non-profit organisation of independent artists and companies (an association with that name operates to this day but has changed completely, although it still pursues the idea of helping non-institutional groups: currently, it primarily supports gay theatre). The organisation was established by Hugo De Greef, who was soon joined by such artists as Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and Jan Lauwers, and that cooperation helped them greatly in creating their early works and to gain international recognition.

At the time, De Greef was the leader of the Kaaitheater, Lauwers was working with his first collective, Epigonentheater (these were the times before Needcompany), Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker founded Rosas in 1983 and created one of her most famous choreographies, Rosas danst Rosas. Schaamte operated based on solidarity and the principle of sharing costs: artists took on management and promotion tasks for all teams, working in jointly rented spaces, and – perhaps most interesting and striking from today's point of view – also shared available financial resources. How? Very simply. They explained it openly at a press conference in 1982: there was one joint bank account from which a given team could draw the funds necessary for financing its current production. Artists who happened to be on tour with their productions and earning money contributed to the account so that others who at that same time were completing work on a production could use it. Then they would set off on a tour with their production and contribute to the shared budget. As the artists explained during the conference: 'This might sound irrelevant. However it is [relevant], since everyone holds great trust in the production of others and is willing to take risks without being directly involved in that artistic production. This gives a clear and important example of how we work and the idea of organisation. As you can see, this is more – and different – than what is expected from a regular theatre management office'.2 This is evidence of how much we trusted one another and assumed risk related to a production on which we didn't even work. Today, several organisations also finance the work of associated teams in a similar way, although they probably do not rise up to such a high level of trust.

Joris Janssens, 'Theatre, Artistic and Research Collectives' conference, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, 19 June 2018. Photo from the recording by Anna Paprzycka.

Bottom-up organisation of cooperation in the artistic environment was another extremely important phenomenon. It is not only about money or management, but also about co-productions, shows, exchanges, mutual promotion and joint activities, including organising festivals. At the time, many artistic associations and centres were created 'out of nothing', but they quickly not only strengthened thanks to collective activities but also managed to merge into international networks (which facilitated raising funds and organising performances abroad). And they constantly pressured the government to allocate more resources to artists operating outside the main cultural institutions.

This started bringing results. Funding from the state budget was increasing. For example, from 1985 to 1992, subsidies for independent dance projects increased from less than five million to thirty-five million francs. Increased subsidies, in turn, changed the way they were working because many artists could then establish and run their own companies. In that decade, Jan Lauwers established Needcompany, for Anna Teresa De Keersmaeker it was Rosas, Jan Fabre started Troubleyn and Wim Vandekeybus began Ultima Vez. But this happened not only because of the flow of funding, but above all because of the flow of new ideas – including those related to organising work and the way of coexisting within the team. Marianne Van Kerkhoven reminded them in 2007:3 'We have reached a level where professionalism has become possible not only in terms of social security, but also professionalism of artistic work. We then become aware that the working structure determines the quality of work'. In other words, your working conditions affect the result. 'Artistic freedom', Kerkhoven added, 'also means the possibility of affecting all parts of the structure in which it is created. And this, among other things, also means deciding how, where, when and with whom you want to work; deciding how you want to reach the audience; deciding on how the conversation with the producer proceeds; how, where and when you want to perform, how your productions will be promoted, and so on'. The collectives aimed at this kind of conscious freedom.

In 1993, the implementation of the Arts Decree began – the act regulating the functioning of arts institutions and consistent support for creators. Firstly, the decree recognised and appreciated the development of performing arts and established centres of art, dance and musical theatre; secondly, it was decided that institutions would receive one-third of the total amount of funds allocated to culture from the state budget (which meant that two-thirds was to be spent on grants); thirdly, a new funding structure was introduced, taking into account the system of long-term subsidies (up to five years). It was indeed a system promoting bottom-up activities: simple, with only a few clear regulations (for example, regarding evaluation methods), probably truly unique on a global scale.

The artistic environment started to develop dynamically (along with the Flemish Wave there was also a phrase, 'the Flemish fast forward'). Flanders Arts Institute meticulously collected the exact figures related to this development (who, when, with whom, what, how many...), so we can compare the 1980s, 1990s and later decades. If you chart the number of artistic events on a graph, you see this great jump of the curve up in the 1990s. There is also a similar increase in the number of active artists – and this trend continues to this day. A clear change also occurred in another area: in the 1980s, most events were produced by one entity (a team), whereas from the 1990s until today, several entities have usually been involved in a given production; there are on average five (and sometimes up to twenty) different partners cooperating on equal terms. The system encourages people to look for collaborators and build artistic ties.

How do independent artists work and live today? For example, the two dancers Trajal Harrell4 and Maria Hassabi5 left New York City (where they had studied and worked earlier) and chose Europe. Not one specific country, but Europe; they are like nomad artists who treat Belgium, France and Greece as their temporary bases. What's more, they are often able to work simultaneously in several places, taking advantage of the opportunities offered by residency programmes, grants, co-productions, etc. They are freelancers working in a flexible and mobile model. Many contemporary artists choose a similar model, but this is also because the whole system has changed. We abandoned stable teams that employed their employees for a long time, in favour of the project-oriented type of work excluding permanent employment. This leads, on one hand, to various ways of building a career path, and on the other hand, to diversification in the area of supporting organisations which take various forms: an institution supporting artists may be a festival, a cultural centre, a centre focused on projects, a centre offering working space (often shared), a private foundation, a state institution, an art laboratory.... However, many artists – although this situation has the potential to develop – have ambivalent attitudes to such a model of life and work, thinking that it is something between the 'offer of adapted support' and 'utopia'. But many also build collectives within such a model.

Today's collectives generate many values derived from the 1980s and adapted to the present situation. In my opinion, the most important are intergenerational solidarity, self-organisation, working in a common space and close ties with local communities. Let's look at the four models of collective operation based on these values. The first is represented by artists from Needcompany and Kuiperskaai, who are present here. Experience and knowledge circulate between the older and the younger generations, especially when family bonds are often built in long-term collectives. But even without them, the teams usually work in one space, because they are connected by common artistic and educational objectives, they provide one another with the know-how on various issues and sometimes the younger gain the advantage of the prestige of the name and reputation of the recognised team whose symbolic capital they can use. The way these collectives function is no less important. They not only work together, but create centres, hubs, platforms: always ready to work with other people, open, inviting.

An example of a model functioning slightly differently is Manyone – a collective composed of individuals (although all are choreographers), of artists who spontaneously organised themselves but do not form a close team. ‘In 2013, artists Sarah Vanhee, Mette Edvardsen, Alma Söderberg and Juan Dominguez created Manyone’, as we read on the website of the collective. 'Manyone is a support structure, a scaffold, helping to organise our work in a sustainable manner and in accordance with the reality of each individual practice.Manyone does not function as a label, but as a collaborative structure that maintains the autonomy of each artist. It is based on the idea of solidarity. The four artists continue to develop and finance their works independently from each other. Our coming together is based on shared affinities and a desire to connect and support each other as artists'.6 A similar collective of individualities is SPIN, consisting of artists who deal not only with art but also with many other issues: they organise public lectures, workshops, establish cooperation with various groups and environments, initiate public discussions, thus critically debating on the position of an artist in society.7 And because they need adequate resources to organise these debates, they manage common finances. Solidarity and trust – these are the basic features of such a collective.

The third model of collective action worth our attention is the model of meeting in a common space. This is not about a permanent relationship, but about creating a certain area of potency, possibilities – quite real, however, creating real bonds. For example, the principle introduced and implemented by a group of Brussels artists (mainly visual artists) was to set one day a month (in this case, every first Monday) as a regular day for meetings of a group of this completely informal network of creators. It worked so well that it has been going on for many years now. Basically, it's about sharing experiences regarding artistic work, extending creative awareness in casual discussion, and sometimes just getting to know each other and support each other. However, very specific joint projects have emerged from this simple idea. One recent project included organising a summer camp for artists who have met to jointly create a special publication called the Fair Art Almanac8 in which they share thoughts, methods and their own ways to implement good practices in art.

The fourth example is the collective K.A.K.9 These are young artists who work with local groups (for example, in squats or in 'troublesome' districts), building with them wider local collectives and trying to solve real problems of residents through joint artistic and social activities. The principle here is long-term cooperation, even for several months, with no initial assumptions – and although the effect is often (along with improving interpersonal relations) a very interesting artistic event presented during the finale, this is not the main goal of the action. Einat Tuchman,10 who once danced in Needcompany, works in a similar manner. From time to time, Einat abandons the artistic environment and works very locally by meeting people and recognising, or rather 'collecting', the talents hidden in them, and then inviting them to cooperate in creating installations (having their dramaturgy) on nearby squares or yards, where residents can exchange their skills. Recently, in one district in Brussels, in Molenbeek (just near MILL, where the Needcompany team is currently located), during a local community festival, she installed a special tent in which voices and sounds from the neighbourhood were recorded – the inhabitants created the sound landscape of their surroundings. In the tent, we could also engage in other activities, sharing what we can do and like doing: Muslim women, for example, offered to sew beautiful bags and backpacks. The benefits of using this strategy include: moving artistic practices from 'art bubbles' (such as centres or galleries) closer to people, inviting them to co-create and launching artistic talents in social contexts.

There are several different strategies for working as creative collectives and many examples of their implementation. Since the 1980s, there have been many transformations, their locations have been moving and the recognition of their own positions in communities and in art has changed. Nowadays, many people actively explore various forms of collectivism, so not only the finances, but also approaches to creative collectives have dispersed.

Presentation by Jan Lauwers (Needcompany):11

I will begin by referring to Joris's presentation, because as a participant of some of these events I would like to add and explain a few things. Schaamte, mentioned at the beginning, was not really a collective and in fact it did not have much in common with the idea of collectivity, at least the one outlined here. First of all, it was organised by one man, Hugo De Greef. He was friends with several artists, closely followed their actions, and since he was a great manager and had leadership skills, at some point he gathered this friendly group and openly declared: 'People, I see that you have no idea about finances or organisational structures! You are artists – and remain artists, I will take care of everything else'. So he founded Schaamte and then Kaaitheater as an association of artists, yes, but he was their boss. That is why I think that the meaning of the word 'collective' is quite difficult to define unambiguously. In my experience, a collective is a structure that must always be led by one or two people. So if we want to talk about Schaamte as a collective, then it's in that sense.

Jan Lauwers, 'Theatre, Artistic and Research Collectives' conference, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, 19 June 2018. Photo from the recording by Anna Paprzycka.

Secondly: when I joined Schaamte, we did have one joint [bank] account for several teams. But it's simply because most of us did not have a so-called personal account; at least I did not have one. I was twenty-something and I didn't care about money. Like others, I was making a living from part-time day jobs: we were taxi drivers or waiters. We lived like this for the next ten years. Epigonentheater, founded in 1979, was my first team in which the idea of collectivity appeared: I wanted to do something with a group of friends. The name of the theatre clearly proclaimed copying the masters, because that's what epigones do. At the time, we believed that practically all contemporary art was copying something that had already been done before; we didn't want to pretend to be inventors, but to act like our predecessors, we wanted to be 'epigones without masters' – even the full name of the company sounded like this at the beginning. There is a contradiction in the wording itself, but it was not so much about us not having masters, but rather about not having bosses. Six months passed and of course the boss appeared. Because that is the reality: there is always someone in the group who feels the greatest responsibility. And that person becomes the boss.

Let's look at the idea of collectives from a historical point of view: let the first example be the Wooster Group – in my opinion the best theatrical collective that ever existed. The group leader was Elizabeth LeCompte, but actually people outside the industry did not even know her name – only the name of the team was commonly recognised. LeCompte was everything to the company, but she never wanted her name to be in the foreground – the team's identification was the most important thing. I did not 'punch' my name for the first ten years of working with Needcompany, either; the team gained fame, but no one knew me. Another interesting example is Rosas – recognisable as a team for years, but then Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker appeared in the foreground. From the beginning, basically no one used the name of Jan Fabre's collective, Troubleyn; there was always only Jan Fabre. The question is, what does this mean for a collective?

In our case, although I was fighting primarily for the recognition of Needcompany, my colleague said after ten years: 'Jan, you have to show your name on the signboard if we want to survive as a team'. So we decided with Grace Ellen Barkey that we would become the 'faces' of the team, which from now on would in fact consist of several teams sometimes working together, sometimes separately and independently. Which is possible precisely because now I am the 'bulldozer' who pushes the whole thing forward, maintaining the financial balance between productions. So we are still a collective, but the presence of this one person who shows initiative and takes on a lot of responsibility is necessary. It has nothing to do with romantic thinking such as: 'Let's get together and see what happens'. We don't function that way and we've never functioned like that. There are no such collectives in the field of art at all. In the team, everyone can have equally strong personalities, but the agreement includes consent for leadership; it's the leader who decides what he or she proposes, and others agree to work together because the leader wants this. In Poland, there are also fantastic artists like [directors Krystian] Lupa and [Krzysztof] Warlikowski who gathered creative collectives around themselves.

However, basically I would define the idea of a collective not from the perspective of existence or non-existence of the leader, but above all by the way of working – by the distinction and the choice between production and reproduction. A repertory theatre is a reproduction machine: someone has written, someone else is directing, the actors have to play what is decided, they have no choice – and it is certainly not collective work. If you choose production (and you are fighting reproduction), you use other tools. Freedom of the collective consists in choosing the method of production. This is what's most important.

Katarzyna Tórz [co-moderator]: So how is it possible that you have been working at Vienna's Burgtheater for years while at the same time believing in collective values? And at the Salzburg opera festival, probably the most conservative stage in Europe....

Jan Lauwers: When Matthias Hartmann,12 the artistic director at Burgtheater, called me with a job offer, at first I rejected it, but he stubbornly repeated his offer for almost two years and eventually we met in person. He assured me then that I would be able to do everything I wanted at the Burgtheater. What's more, he stated that he wanted me to knock the actors out of their previous work mode and sense of comfort. Actors at the Burg[theater] are great artists, but they are artists of reproduction. In addition, the way of working in that company is deadly, because every evening a different production is performed: Chekhov on Monday, Shakespeare on Tuesday, Molière on Wednesday, etc. An outstanding, regularly cast actor plays six different plays, six different roles a week. How to survive in this extremely reproductive system? If an artist is deeply invested in every performance, putting his or her soul into it, they could commit suicide – which happens – because this is unbearable. Actors thus separate 'themselves' from the 'role', they play cold, try to preserve the 'privacy in their heads', eliminating their personality from the stage. And then I come to them from a company where you always ask about who you are – 'you as you' – because on stage you first become 'you yourself'. And only now can you play Macbeth. The actor who reproduces says: 'No, I will not play like that because it's too narcissistic'.

Matthias Hartmann wanted me to free actors from such thinking. It was not really a job, but rather a struggle.... In 2012, when I directed Kaligula, a fantastic actor from the Burg, Cornelius Obonya, played the lead role. After three weeks of rehearsals, he said: 'If we continue working like this, it will not work out'. But soon he began to understand what was going on, and he found himself in an unusual mode of creation. But most actors gave up, we could not communicate. After almost five years, I had to leave Burgtheater because I became a teacher there. Firstly, I never wanted to do this, and secondly, I did not achieve what I was planning to do with the reproducing actors. I realised that it wasn't possible. It is, after all, a completely different kind of theatre. But the Burg is very rich and paid me twenty-five thousand euro a year, which fed the Needcompany fund – and thanks to that we survived. The Burg simply sponsored us: I was in Vienna, but the collective continued to work – it was a great deal. But it could not last any longer....

The opera in Salzburg was a different case. The director of that institution [Markus Hinterhäuser] is a fantastic artist; if you've ever been to one of his piano concerts, you know what I'm talking about. When he found me, he announced that he was going to change the whole world of opera13 – and asked if I would like to join him. I replied that I would not. He accepted this refusal, then added that in that case, he would ask me to at least direct Monteverdi. I agreed right away. Why? Because Monteverdi expressed exactly the same thing I am talking about now: production and reproduction, creation and recreation. The whole baroque [period] was in my mind a fight against reconstruction. Operas were performed differently every evening – Monteverdi did not give the musicians exact scores, he only wrote a few notes; it was like jazz, it provided great freedom. In the baroque, the conductor did not wave his hands rhythmically leading the orchestra....

Question: how to play this today, and why do we still think we are discovering something new, since this problem of creation and reproduction was already been recognised in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries? Nothing new under the sun – it's still just replays. Since the theatre of reproduction has appeared, it is very difficult today to find Monteverdi's freedom on stage – but you can try working collectively: everyone in the band has equally important function and the same creative space, the conductor is part of the team, the director does not tell anyone if they are supposed to enter from the left or the right, the singers search for their own ways of expression. We are trying to establish new, non-hierarchical relations – and at the same time we are investigating how these can be interpreted in a work which after all speaks of cruelty and power.... In short, I agreed to Salzburg, with the same financial agreement as in Vienna: money for Needcompany. But I must also add that these were decisions made after talking to specific people: institutions did not ask me, artists I value asked me.

KT: So I understand that these were not compromises, but rather it was about an infecting of institutions. You could have changed something in them.

Agata Siwiak [co-moderator]: I think that there are two points of reference in defining collectivity: one is determined by the system – organisational and financial – and the other by ways of working: acting collectively, creative group. Here we are now more interested in matters of organisation and finances, or more precisely in the distribution system: if in Poland ninety-five per cent of subsidies are spent on repertory theatres, working in a collective means that you become a precarian or volunteer.... We're interested in how one can create a good system supporting independent groups.

JL: Let's talk about the [organisational] framework. The core of the Flemish system is the international approach. We are a small society, we have to cooperate with others, our work is based primarily on international contacts. We are not just 'Flemish' but international. We don't work solely 'for ourselves'. According to my observations, it seems that in Poland, repertory theatre is still intended basically only for Poles – that's the kind of thinking we abandoned in Belgium a long time ago, in the 1980s or 1990s. Of course, the dynamically developing festival system contributed to this at that time. Now it's harder because festivals have been taken over by big institutions that have multilateral agreements between them – if you're not in this system, you're not there at all. Without participation in the festival cycle, Needcompany would disappear very quickly from the face of the earth. Nevertheless, the basic Flemish system of distributing funds between institutional theatres and independent collectives is still, in my opinion, one of the best in the world, or at least one of the most democratic. Everyone can apply for a grant from an equal basis, regardless of whether they are a name-recognition artist or just a beginner. However, I emphasise its two important aspects: internationalisation and the festival system as helpful and contributing to the development of teams.

AS: For you, Lisaboa [Houbrechts], was joining a collective and choosing this way of artistic activity also something obvious? When you started working at Kuiperskaai14, you were only twenty-one.

Lisaboa Houbrechts: No, it was not obvious at all, because contrary to appearances, I had been looking for my own way for quite a long time. I studied at a university where there were really many individualists around me, working separately. When I met – at school – Victor [Lauwers], Romy [Louise Lauwers] and Oscar [van der Put], my present colleagues, we began to discuss a lot and it turned out that we had a good influence on each other. We watched our works, which was interesting, because each of us specialised in something else: Victor wrote and made films, Romy was a performer, Oscar painted, I was acting. We decided to rent a large atelier in Ghent and unite our various skills in collective work.

The work of my colleagues inspired me immensely. We started with the fact that we had prepared several exhibitions in this large space, and I started working with Romy, directing her and my first small plays. Atelier, where we lived, worked and presented our achievements, quickly began to attract other students and became an often-visited place; maybe an 'artistic' myth was even created around it. Several other collectives soon appeared: I got the impression that it was a kind of reaction to individualism pushed through at the university, and even a kind of protest against school work methods. Anyway, when we showed one of our productions at school, it was rejected – it was not the way we had been taught. Our international performances were also scowled upon. But later, the school also appreciated Kuiperskaai's work – interestingly, one of its directors later became a member of our team. So I think that our collective was created to some extent against the hierarchies in art, guarded by the school, and from mutual fascination when we discovered that we could cooperate in a joint effort and achieve good artistic results.

AS: You could say that you have implemented one of the basic conditions of the collective: you chose the people with whom you wanted to work. In repertory theatre, that is impossible.

JL: In Belgium, it is in fact possible, because in the 1990s the system of work in repertory theatres was changed. At that time, all the full-time jobs were liquidated, actors became freelancers, the director of a company decided about wages and period of employment. So in a sense, everyone became free again and it became quite possible to create a strong team of people declaring their willingness to cooperate. Although, of course, at the beginning the actors were in shock, because after years of working full time, some of them had to find themselves in this completely new system. On the other hand, such a move was necessary, because in theatre companies there were many full-time actors who were getting a salary, but they did not perform at all. It was the same in other places: when the new director of the Burgtheater took the job, he told the company he wanted to make the first production only with actors who were employed there but had not gone on stage for more than five years. Twenty people reported!

Participants, 'Theatre, Artistic and Research Collectives' conference, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, 19 June 2018. Photo from the recording by Anna Paprzycka.

Małgorzata Jabłońska: I would like to ask about social security. When we listen to your experiences, probably each of us would be willing to enter into this flexible system – but what does the social-security situation look like? And how did actors who worked for years in full-time jobs endure this sudden 'freedom' depriving them of their steady income?

JL: Very bad, let's be honest. Especially older actors had trouble finding their way under the new conditions – some of transferred to TV: that's when lengthy TV shows appeared. After all, all theatre artists are rather poor....

Johan Penson:15 In Belgium, there is special insurance for seasonal workers – for example, fishermen, foresters and people who work intensively only for a certain period of the year. This also includes actors. Artists who can prove that they work only seasonally are granted special status and for the rest of the year they receive a guaranteed payment in the amount of minimum subsistence. Which does not mean that they stop being poor....

MJ: We have this image that artists from the West are rather rich. It's good to know it's not real.

JJ: Of course there are distinctions and categories organising the 'types' of artists: actors, set designers, etc. Their earnings also depend on additional subsidies that are granted.

MJ: Subsidies directed to the institution in which they work?

JJ: No, it's about individual grants. In Belgium, each artist can write a project and send it to the ministry, to a special commission which provides operating grants. This is, for example, how Kuiperskaai still works. The Flemish system is, as I see it, very comfortable compared to the one in Poland; however, we are a much richer society and we can allocate more resources to the arts.

MJ: But if I apply for and receive such a grant, can I guarantee a fair salary to my colleagues for a while?

JL: Yes, but of course only for the duration of that project. This is clearly defined at the beginning, and the periods are: six months, a year or a maximum of five years. The subsidy is never granted for an indefinite period. However, any artist working outside the institution, a freelancer, if he or she does not work on any project at the moment, can count on state aid on average for three months a year – this is the guaranteed minimum subsistence.

MJ: I will say for comparison that projects in Poland are often assessed only according to the total amount of planned costs: of course, the lower the budget, the better the project. Nobody cares about what artists will live on.

JJ: In Belgium, of course, the planned budget is also an important element of the project evaluation, but it remains only one of the criteria. In artistic matters, there is full freedom, but in the description of the project you need to specify very carefully issues related to the administration of the allocated funds. I would add, however, that the operation of collectives is becoming more difficult, because the number of them is growing – although to someone looking from the outside, the conditions of independent Flemish teams may still seem luxurious.

JL: The functioning of teams is often also related to political choices. Let's ask, for example, how did the Needcompany team appear in Poland? After all, not thanks to your minister of culture, but thanks to ours. When the Malta Festival announced that we would be curators of this year's edition, the Polish ministry immediately took away half the funds from the festival – foreign curators were not appreciated. The Malta directors went to the Flemish Minister of Culture, described the situation and the minister agreed to pay for our stay in Poland.

That is, our minister of culture gave the festival money, so he made a political decision, because your minister of culture had also made a political decision.16 What's more, our minister will visit the festival in a few days – but it will not be a state-level visit, and the ministers will not meet. However, if our future minister of culture would be as retrograde as your current one, then certainly the subsidy system would also change. So we always have to take into account the political dimension of the situation. Of course, I wish you a great minister of culture.... Let's take the German system, which allocates huge sums to the theatre – a single municipal theatre receives a subsidy equal to the entire budget of Polish (and Flemish) culture – and that is also their conscious choice.

JJ: We have reached the high 'national' level in this conversation: we're talking about how it is done in Flanders and Poland. Maybe we should get down to the local level, because, as I understand it, even subsidies granted locally, and not at the state level, are more important for the Malta Festival. Governments and ministers do not always want to invest in such abstract and uncertain areas as art, but at the local level it looks different. I don't even have in mind artistic autonomy, but rather relations within communities, about the emerging new dynamics of activities. And maybe this is a better place to talk about values that art brings in local contexts; I'm afraid we may still lack the proper language to describe what is happening at this level, but I think that a new quality emerges from connecting the international and the local.

AS: And what specific institutions are responsible for giving grants in Flanders? Is it only the ministry of culture?

JJ: It depends on the place, because different districts and cities have their own systems. Municipal theatres are also treated differently, although at the local level, subsidies are most often divided in half – between municipal institutions and independent companies. But you could say that subsidies are granted by the government, city councils and provinces. However, in the government, the ministry of culture never decides, but always works in agreement with other units, because it shares responsibility for the budget with them.

Zofia Smolarska: You had said that the company manager convinced you to display your name on the 'marquee', which was to help in promotional activities....

JL: Yes, and in my opinion it was connected with individualist approach developing rapidly in the 1990s: people wanted specific names, they needed stars. The name of a person sounded better than the name of the company. It was a purely commercial decision.

ZS: ...and what, it worked? Can you show this in numbers? Was it easier to get subsidies?

JL: It's hard to say.... However, we did it and we continue to work; I don't know what would have happened if we did not decide to do that. In any case, the individualist approach in art in general is quite a recent matter; painters began to sign pictures only in the Renaissance....

ZS: But there are still such companies, collectives, which we think of as a group of people connected by a bond; we do not know who the boss is and whether there is one at all. I'm not just talking about artistic collectives. This happens even in cases of large commercial companies: we know the name of IKEA or Mitsubishi, we do not know their boss or owner.

JL: Oh no, that's where the one person is everywhere. Let's think about it differently: IKEA has already become a person. It's an institution – individuality.

ZS: So why can't Needcompany be like that? A collective without Jan Lauwers as the 'face' of the company.

JL: I've always wanted it to be like that. A good example of how wanting to do something does not always mean that you can is Les Ballets C de la B and Alain Platel, the famous choreographer. A few years ago, Alain wanted to give the company a free hand and the opportunity for independent development; he announced that he was leaving. And what happened? The company immediately lost half of the subsidy and almost ceased to exist. Alain Platel hurriedly announced that he was staying. Something similar might have happened to Needcompany.

So what we do today is primarily investing in young people like Lisaboa and Kuiperskaai. I know that in a few years, I will no longer be the boss and director; I do not want to leave the company, but I also do not want to be the one who pushes everything forward any more. I want to be a free artist again. It will take about five years to prepare the ministry for this step; I want to disappear discreetly and silently, so that in five years they will realise: Oh! he's not there any more? and look, the company works anyway! This is to say that making Needcompany a stable institution is much more difficult than exposing my name or not.

JJ: This is again a matter of economics and finance, which has a lot in common with a more general movement: the transition from 'stable companies' to 'project work'. Until recently, the symbolic capital and prestige of companies were important in establishing cooperation between them and artists, but today – perhaps over the past twenty years – the names matter more. Often, next to the name of the company, collaborating artists are mentioned, because it is important to indicate that they took part in the project by bringing in their individual talents and capitals.

Conference participant: Maybe a good contribution to the discussion about collectives in Poland would be to check how many of them, next to the name of the company, also use a strong artist's name? I think that this greatly strengthens the team's punching power.

AS: You said that you believe in a democratic system of financing collectives, supported by implementing the right policy, and that you absolutely do not believe in the romantic myth that collectivity automatically means democracy. Is it because a strong personality will always dominate and we should be okay with this?

JL: I think so. But regardless of that, we respect each other in the team and everyone – I emphasise, everyone – feels great responsibility for the whole collective. In this sense, everyone is also their own boss. Every week, we sit down at the table and in turns report the work done; it's a strict and, I have to admit, quite stressful system.

JJ: In my opinion, the issue of a variety of skills and talents is more important than the domination of a strong personality. People can share them, and we need those who know and can do something other than ourselves. Collectivity is for me more a history of combining differences, which becomes a value.

JL: Needcompany's structure is actually very technical, but every day we face a challenge: how to lead the team? A few years ago, during a difficult time, I asked Grace Ellen Barkey if she would like to become the Needcompany boss. Ellen did not agree because she thought she would lose all her freedom. I asked the same question to Johan, who replied that thinking about some 'full-time' boss was a mistake, because freedom – the freedom of everyone in the team – will evaporate. Johan suggested that he would be a manager two days a week. I was amazed by this approach, but we introduced such a system and it worked. When there was no boss for three days, everyone was supervising their work and was responsible for it, while for those two days when the boss was there, everything could be determined with him. At the time, Johan was conducting serious research on new management methods, and Needcompany was an experimental field for him. This experiment has been so successful that we keep working this way: the manager operates two days a week.

MJ: The artistic potential of working in a collective is great, but I am still wondering about the position of the leader – the one with the name better known than the rest of the company – who also, let's say, engages in work outside the company as a director. And it turns out that he is not a good director at all, that it was the sum of the work of the members of the collective that determined artistic achievements. Then you could see that he was as 'good' as the value of his collective and not of his own individual talent. But my question is different: if we establish a collective and work in it, why bother engaging outside?

JL: When I went to Salzburg, I acted like many other directors who work outside their own team, not only to take on new artistic challenges, but also to support the team financially. Nevertheless – it is always a choice.

Johan Penson and participants, 'Theatre, Artistic and Research Collectives' conference, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, 19 June 2018. Photo from the recording by Anna Paprzycka.

JP: I would like to add that it happens that the collective works fine at the beginning, but when the world created by the group becomes too 'settled', the time comes for changes. I would not worry about collectives dying – we'll all die one day. So while you still have strength, start working somewhere else, create a new team. Besides, you learn a lot more when you fail than when you succeed, right? It is very important to keep trying.

MJ: However, we have many examples of a very long cooperation of one team: Odin Theatret [in Denmark], Teatr Ósmego Dnia [Theatre of the Eighth Day, in Poznań], companies working for nearly twenty or thirty years in almost unchanging compositions. It also once built the ethos of teamwork. I have the impression that today we are at a turning point – to a great extent, the project system changes and destroys this potential durability.

JP: But it is on such occasion that we must emphasise the role of the leader: someone strong, who keeps the team, pushes it forward. However, in my opinion, 'bossing' applies to every level of work and has a great impact on the sense of freedom of the members of the collective, their enthusiasm for work, readiness to fulfil their tasks. Someone who cleans the room must have a sense of bossing in cleaning the room – then the leader of the collective will be able to trust everyone and to assume that they will do their job well. A good leader will make the bossing at each level contribute to the operability of the entire team, because everyone will feel that they are important and responsible.

KT: Last question. You have been operating for over thirty years and now you have opened a new chapter, partly due to moving to MILL, partly because of a new type of work with the local community [MILL is the location in Molenbeek, a multicultural district of Brussels, where Needcompany has had its new home for over a year]. You work differently than before: you are open to the public, a lot of people come to you, several groups work in the building. Is there a limit beyond which, in this mode of operation, doubts may arise about maintaining the collective, its cohesion, responsibility for itself and others? Doubts about whether you would not transform from the old collective into an institution and lose something important?

JL: We have moved to MILL exactly to not become an institution, to not ossify by accident. We abandoned the peaceful centre of Brussels and moved to Molenbeek, a multicultural area, but – as you know from press reports after last year's terrorist attacks [at Brussels Central Station in June 2017] – a dangerous place associated with crime, considered a hellish place. Nobody – if they don't have to – wants to live there, so we could afford a great seat of operations, because Molenbeek is very cheap. Many artists moved there, not only because they can afford it, but above all because they are not afraid of immersing in multiculturalism and they feel social responsibility.

Our migration to Molenbeek, however, did not happen with the intention of changing Molenbeek, but to change ourselves. I worked for twenty-seven years in the centre of Brussels, then spent some time abroad and I felt that Needcompany had to change. But I did not do anything special, it just happened. Of course, there was a decision behind our move – and the choice to open the door. We talked about it a lot: that now we will invite people, share our space, work together, cook meals together with refugees – which meant that Johan, though he is a manager, will also be standing by the kitchen, and Ellen, although a choreographer, will also wash the dishes. This openness to others has also helped us to get to know each other better; we came to the conclusion that opening the door – and sometimes closing it for some time, which is also very important – in every sense, turned out to be good for us. It helped me to rethink the objectives of art and its location in society. But, let me emphasise this: you always have a choice.

Translated by Monika Bokiniec

Panel participants:

Lisaboa Houbrechts obtained her Master’s in Drama from the School of Arts Ghent|KASK Ghent in 2016. She writes and directs. Together with Victor Lauwers, Romy Louise Lauwers and Oscar van der Put, she founded Kuiperskaai. With that company she among other things has made De Schepping/The Creation (2013), The Goldberg Chronicles (2014), The Winter’s Tale (2016) and 1095 (2017). She evokes history and classical repertoire in the form of a ritual, and reveals human nature as a series of passionate urges.

Joris Janssens is research&development coordinator at Flanders Arts Institute, the supporting organisation for the arts in Flanders. Since 2001, he worked at the Vlaams Theater Instituut (Flemish Theater Institute), first as researcher and until 2011 as director. VTI has recently merged with the institutes for visual art and music to become Flanders Arts Institute. He holds a Ph.D. on Linguistics and Literature: Germanic Languages from the KU Leuven. In 1997-2001, he worked at the KU Leuven (Department Literatuurwetenschap, Netherlandic Studies). In 2001, he worked at the University of Vienna in the Department for Nederlandistik. He has published and edited several books and articles on performing arts practice and policies, literary history and pop culture.

Jan Lauwers is an artist who works in just about every medium. Over the last thirty years he has become best known for his pioneering work for the stage with Needcompany, which was founded in Brussels in 1986 […]together with Grace Ellen Barkey. Maarten Seghers has been a member of Needcompany since 2001. Lauwers, Barkey and Seghers form the core of the company, and it embraces all their artistic work: theatre, dance, performance, visual art, writing, etc. Their creations are shown at the most prominent venues at home and abroad. […] Since the very beginning, Needcompany has presented itself as an international, multilingual, innovative and multidisciplinary company. This diversity is reflected best in the ensemble itself, in which on average 7 different nationalities are represented. Over the years Needcompany has put increasing emphasis on this ensemble and several artistic alliances have flourished: Lemm&Barkey (Grace Ellen Barkey and Lot Lemm) and OHNO COOPERATION (Maarten Seghers and Jan Lauwers).

Małgorzata Jabłońska is a theatre scholar specialising in performer training and the history of performer training, and methodology of writing about body dramaturgy within a theatre performance (with a special focus on alternative theatre). She is a Ph.D. student at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, working on a thesis titled “Ku dramaturgii ciała. Pływ biomechaniki Wsiewołoda Emiliewicza Meyerholda na koncepcje treningu aktorskiego w teatrze europejskim XX wieku”. She works regularly with the Grotowski Institute in Wrocław, where in 2013 she organised Praktyki Teatralne Wsiewołoda Meyerholda, Poland’s first international Vsevolod Meyerhold conference. She has co-ordinated scholarly projects as part of the Wrocław 2016 Theatre Olympics. She is co-author of Trening fizyczny aktora. Od działań indywidualnych do zespołu (Łódź 2015). She is a member of the Polish Society for Theatre Research, Poland’s Theatre Offensive association and the International Society for Performer Training.

Johan Penson is the general manager of Needcompany.

Agata Siwiak is producer and curator of the project Wielkopolska: Revolution (2012-2014). Theatre curator and producer. Graduated in cultural studies and cultural institution management from Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań. In 2008 and 2009 joint director (with Grzegorz Niziołek) of the Łódź of Four Cultures Festival. Curator of the Trickster 2011 project – the performance programme of the prestigious European Cultural Congress in Wrocław. Teaches a specialisation for theatre curators at the Department of Theatre, Drama and Performances of the Adam Mickiewicz University.

Zofia Smolarska is a theatre scholar the Theatre Academy in Warsaw. Graduated from the Theatre Academy in Warsaw, where she now works as a lecturer at the Department of Theatre Studies. Deputy chair of the Polish Association for Theatre Studies and member of the Polish Theatre Journal’s editorial team. Author of a book Rimini Protokoll. Ślepe uliczki teatru partycypacyjnego [Rimini Protokoll. Blind Alleys of Participatory Theatre]. Along with the present journal, her articles have appeared in Teatr, Didaskalia, Dialog, Performer, on dwutygodnik.com, in Svet a Divadlo, Rzut, Art&Business and in academic monographs. The participatory aspect of the creative process is among her main interests (practical as well as research). An urban performer and author of urban social projects, she has collaborated with the Rimini Protokoll collective and with Edit Kaldor on participatory theatre projects. Her book Rimini Protokoll. Ślepe uliczki teatru partycypacyjnego was published in 2017.

Katatrzyna Tórz works as programme co-ordinator for the Malta Festival in Poznań, and is co-author of its Malta-Idiom strand. She works at the programming department of the National Audiovisual Institute in Warsaw. She holds a degree in Philosophy from the University of Warsaw, a postgraduate degree in Cultural Diplomacy from Collegium Civitas, Warsaw’s private university, and completed the European Atelier for Young Festival Managers training programme. She participated in the SPACE – Programmers on the Move project. Her work has appeared in journals including Teatr, Notatnik Teatralny and the Dwutygodnik online magazine, where she is editor of the section Produkty uboczne [Byproducts].

1. Flanders Arts Institute is a Flemish 'research centre and institution combining such arts as music, visual and performing arts', based in Brussels: https://www.flandersartsinstitute.be. Joris Janssens is a member of the Institute team, working as Head of Research and Development.

2. It is obviously something more – and something else – than typical theatre management.

3. Marianne Van Kerkhoven (1946–2013), essayist and dramaturge. In 1970, she established Het Trojaanse Paard, the collective which played a significant role in Flemish political theatre. She was an active participant in the Flemish Wave, the rapid development of performing arts in the 1980s, and collaborated as a dramaturge with such artists as Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, Jan Lauwers, Jan Ritsema, Josse De Pauw, Guy Cassiers, Peter Van Kraaij. She edited magazines devoted to performing arts, Etcetera and Theaterschrift, and wrote many articles on dance, theatre and performing arts. In 2002, a collection of her writings was published, Van het kijken en van het schrijven [On Looking and Writing]. For further information: http://sarma.be/pages/Marianne_Van_Kerkhoven.

4. Trajal Harrell (b. 1973), American dancer and choreographer. His most famous piece is the seven-part dance essay Twenty Looks or Paris Is Burning at the Judson Church, in which he combined early postmodern dance with contemporary voguing. See: https://betatrajal.org/home.html.

5. Maria Hassabi, born on Cyprus, educated in the US, dancer, choreographer, visual artist working in galleries, museums, showrooms and public spaces all over the world. See: http://mariahassabi.com.

6. See: http://www.manyone.be/about.html.

7. See the collective's website: http://spinspin.be/about.php, where the artists define themselves in various ways: as a collective, artistic platform, research team, but also as a 'mobile body', 'mess' and 'playground'.

8. To be published in 2019.

9. 'K.A.K. (Koekelbergse Alliance van Knutselaars) is a loosely connected alliance of hobbyists, theatre artists, thinkers and other enthusiasts. Somewhere on the margins, K.A.K. creates its own working conditions and creates the platform for dialogue within and with others.' See the collective's website: http://www.k-a-k.be.

10. Einat Tuchman is a dancer collaborating closely with several acclaimed companies, including Les Ballets C de la B. She has been developing her own projects (the solos Turn Off the Light and I Died a Hundred Times; the performance Oh, Boy, to which she invited four male dancers to see if the idea of 'developing a team' would work out in such a configuration). She is mainly interested in studying dance built from everyday, mundane actions and gestures.

11. The Needcompany team established by Jan Lauwers in Brussels has been operating since 1986. Many of their productions reflect the idea contained in the name: the focus on contact with another person (the title of the anthology of texts about Lauwers' theatre work from 2007, No Beauty for Me There Where Human Life Is Rare, was taken from Camus' Caligula) and the need to cooperate, to create in a team. From the beginning, it has been a multidisciplinary and international team, which includes smaller collectives (such as Lemm&Barkey and Ohno Cooperation). The most renowned productions include The Snakesong Trilogy (1996), Isabella's Room (2004), the trilogy Sad Face/Happy Face (2008), Shakespeare productions (since 1990), and the recent The Blind Poet (2015) and War and Turpentine (2017). The team has toured often in Poland; at the Malta Festival in 2018, Jan Lauwers, Grace Ellen Barkey and Maarten Seghers curated the festival programme (the 'Leap of faith' idiom).

12. Matthias Hartmann was artistic director at the Burgtheater from 2009 to 2014.

13. Markus Hinterhäuser served as artistic director of the Salzburg Festival in 2011, and since 2016. The programme of 2018 festival may serve as evidence of his efforts. Along with Jan Lauwers's production (The Coronation of Poppea), it included opera productions directed by Krzysztof Warlikowski (Hans Werner Henze's The Bassarides) and Romeo Castelucci (Salome by Richard Strauss).

14. Lisaboa Houbrechts is a director in the Kuiperskaai collective, which she established in 2012 with Romy Louise Lauwers, Victor Lauwers and Oscar van der Put. The collective, consisting of writers, visual artists, dancers and actors, works at MILL, the Needcompany centre in Molenbeek. At the Malta Festival in 2018, the Kuiperskaai team showed their most recent production, 1095 (by Victor Lauwers, dir. by Lisaboa Houbrechts); the title refers to the year that Pope Urban II initiated the first crusades.

15. Johan Penson is the general manager of Needcompany.

16. An excerpt from the curatorial text by Jan Lauwers, Grace Ellen Barkey and Maarten Seghers published on the Malta Festival website: 'The Polish government representing right-wing and nationalist views, gravely limited the financial support for the festival, pushing it against the wall. The director of the festival, Michał Merczyński, asked Needcompany to support the festival with their prestige despite this situation. The limited programme curated by Needcompany includes: the new concert-performance by Maarten Seghers, Concert by a Band Facing the Wrong Way, the English version of War and Turpentine, FOREVER by Lemm&Barkey, The Moon by MaisonDahlBonnema, 1095 by Kuiperskaai and Another One by Lobke Leirens and Maxim Storms. The festival will be opened by the Flemish minister of culture, Sven Gatz'. See: https://malta-festival.pl/pl/program/idiom/tekst-kuratorski-brgrace-ellen-barkey-jan-lauwers-i-maarten.

Filled under:

artistic collectives; democratisation; institution; performing arts;theatre collectives